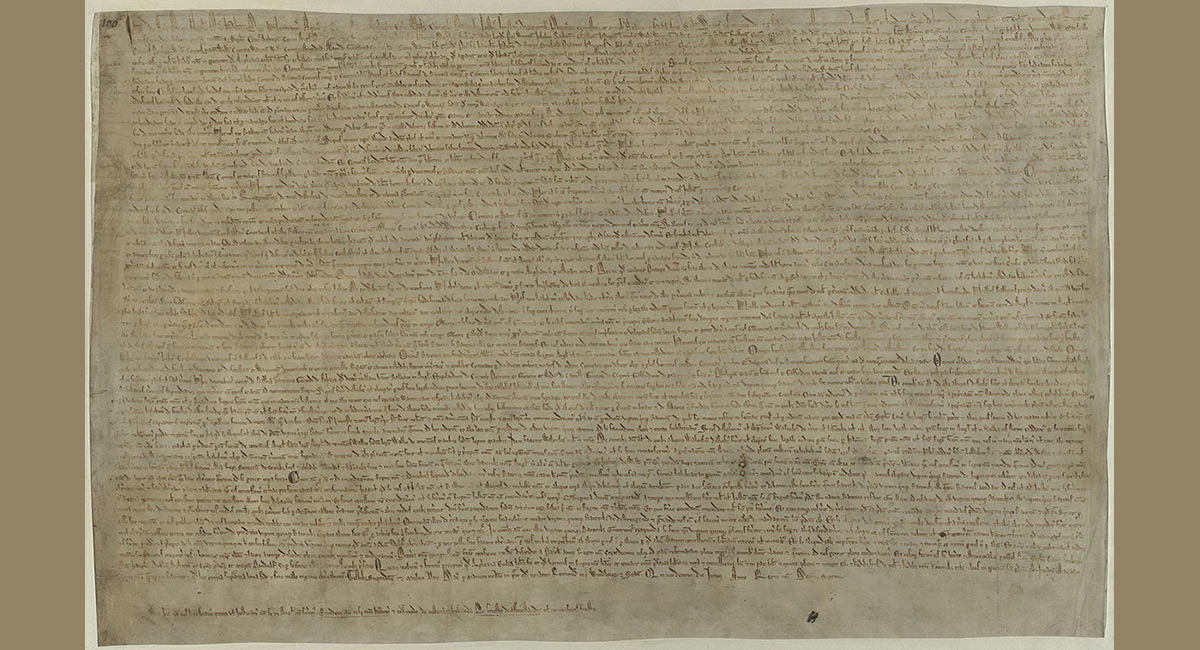

This month marks the 800th anniversary of the signing of the Magna Carta in England. The Magna Carta, or Great Charter, was important for several reasons. First, it was a treaty intended to establish peace between the highly unpopular King John and various factions of rebellious barons. (It did not work.)

But the Magna Carta signifies something much more important in the history of the West. Until the Magna Carta, the king was absolutely above the law, able to create and enforce laws and decrees without giving any thought or credence to custom, social norms, or existing decrees. Citizens faced the real possibility of having one law governing an activity one day and a different law the next. The signing of the charter was a legitimate attempt to establish a predictable and consistent rule of law—at least for the free men of the realm.

Not long after its adoption by King John, the pope annulled it at the king’s request. Although the treaty did not take hold initially, it would be later used to engender major political reform. The various clauses of the Magna Carta would inspire laws we now take for granted, like religious freedom, protection from false imprisonment, and the right to a trial by jury. This is not to say the drafters of the charter were staunch advocates of liberty. On the contrary, the rebel barons were aristocrats interested in their personal gain and not the freedom of all people.

The Magna Carta is one of the first well-known treaties to address the “paradox of government power,” the idea that for the government to perform particular functions, citizens must simultaneously empower the government and constrain its ability to violate individual rights.

The Founding Fathers understood this paradox well and attempted to solve it much like the authors of the Magna Carta. Recognizing that those in power tend to try to expand their reach, both documents established checks and balances that would, in principle, keep one part of the government from becoming too powerful. This is particularly important to consider in the modern context. In recent years, we’ve seen a significant erosion of the constraints placed on government leaders. In fact, Americans have actively advocated increased government power, often in the name of “defense” or “public safety.”

Consider, for example, the plethora of executive orders issued in the name of combating terrorism, poverty, and immigration. Many of these mandates have garnered significant public support although they grossly expand the power of the president. In fact, these proclamations allow the president to expand his authority in some 160 areas, including freezing individual’s assets, confiscating private property, and limiting trade. In the most extreme cases, they allow the president to suspend habeas corpus, meaning the executive can arrest, detain, and imprison U.S. citizens and others without judicial review.

Throughout the war on terror, our liberties have eroded at an alarming rate. In addition to the expanded powers of the president, agents of the Transportation Security Administration search you and your belongings every time you fly. The National Security Agency can keep records on every email you send. Collection of our phone data has only just been curtailed. Your local police department can track your phone calls in the course of searching for the records of a “person of interest.” All these things occur with minimal or no oversight.

Those who forced the Magna Carta on King John were willing to fight for what they believed was so important, and despite its annulment, revised charters were later issued by John’s successors. We also should be ardent defenders of our liberties. While waging civil war is not necessary, it’s important to remember that preserving the checks and balances placed on our government is essential if we want to preserve the freedoms we hold so dear.

As we remember the Magna Carta, we should not only reflect on the freedoms we enjoy; we should remember that these freedoms are preserved and protected not by the government officials who look to expand their power, but by each of us as free citizens.