Since the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, most countries have witnessed a rapid runup in inflation followed by hasty retreat. For some nations, the trip’s been a wild rollercoaster ride, a lurching ascent towards a summit where the houses below look like Monopoly pieces, followed by a steep, head-spinning drop. For others, the journey has resembled a snowmobile’s wintry climb up a low, sloping hill, and the gliding descent down the other side. Only the general, up-and-down pattern is the same. But some nations never experienced a steep inflation jump at all. Put simply, “Big Inflation” wasn’t a global phenomenon.

Our research into the link between money supply and inflation in 27 countries since 2020 shows that where the roller-coaster scourge happened, as in the U.S., the cause was a huge, misguided spike in the money supply. In countries where M2 (a measure of the money supply that includes cash, checking deposits, and other deposits readily convertible to cash) rose only gradually, the price rise proved moderate and didn’t require draconian, potentially growth-crushing measures to correct.

While the inflation rides have varied a great deal across geographies, the refrains about their sources have not. Officialdom and the chattering classes have all sung the same song: Inflation was caused by a plethora of non-monetary factors, ranging from supply chain glitches to COVID-19 lockdowns to oil price spikes. Once these factors receded, so did inflation.

Absent from the standard script is the role of money. For example, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), in its recent Annual Economic Report, highlights five lessons learned from the post-COVID waves of inflation. But nowhere to be found is the role money supply played.

Such a reaction by central bankers is typical. After all, no one likes to take the blame for causing inflation. For central bankers, it’s the old adage: It’s not me, it’s the guy behind the tree.

Academic cover for the central bankers’ version is provided by the current fashion in macroeconomics. Money is absent from the post-Keynesian models that have been en vogue for the past 30 years. That wasn’t always the case. Back in 1985, when Gottfried Haberler penned his influential The Problem of Stagflation, he wrote: “I fully agree with the monetarists that inflation, including stagflation, is basically a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that there has never been a significant inflation or stagflation—prices rising, say, by 4 percent or more a year for two or more years—without a significant growth in the stock of money.” What Haberler wrote in 1985 is as true today as it was then.

We examined the link between changes in the stock of broad money and inflation in 27 countries during the 2020-24 period. These countries account for over 75% of the world’s GDP. They range from large developed to smaller emerging market nations. To compare money supply and inflation data, we used a 12-month moving average of the year-over-year percentage changes.

We found a very clear pattern in all cases. First, the rate of growth in the money supply changed. Then, with a lag, inflation changed its course. The amplitude of the inflationary ramp varied from wild to mild. The wild upward swings happened in the U.S., U.K., Eurozone, Denmark, Sweden, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, Brazil, Egypt, Ghana, Israel, Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Turkey. The up-and-down ride was mild in China, Japan, Switzerland, Malaysia, India, Indonesia, and South Africa.

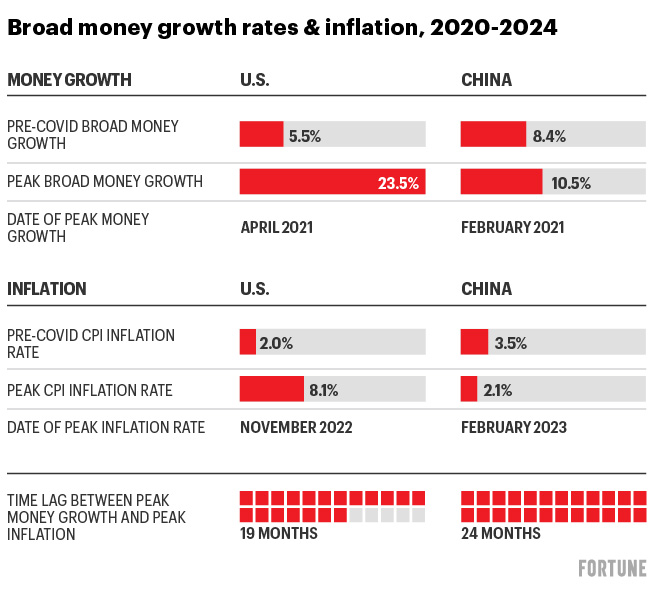

The two largest economies in the world, the U.S. and China, illustrate that inflation isn’t universal but rather dependent on the rate of growth in each country’s money supply. In the U.S., we find that the rate of growth in the money supply soared after COVID-19 hit, peaking in April 2021 at a pace over four times more rapid than pre-COVID. Nineteen months later, the U.S. inflation rate peaked at 8.1% and was also over four times higher than its pre-COVID rate. That’s a theme park-level, rollercoaster liftoff skyward that leaves the whole family breathless.

In contrast, China didn’t experience much of an upward ride at all. Its money supply growth rate didn’t change much after the pandemic hit, reaching its peak in February 2021. With a 24-month lag, China’s annual inflation rate peaked at only 2.1%.

The recent ups and downs in inflation echo Milton Friedman’s dictum: “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” They also mirror Friedman’s findings on the lag of roughly two years between changes in the stock of money and changes in inflation. In the 27 countries we studied, the mean and median lags witnessed in the 2020-24 inflation rollercoaster were 23.9 and 23 months, respectively.

Having failed to predict the recent ups and downs in the course of inflation, central bankers and contemporary macroeconomists should throw away their scripts and models and start paying attention to the strong causal link between changes in the stock of money and inflation.