The City of Oakland announced recently that it has been awarded $7.2 million from the state to help residents of two homeless encampments. Officials optimistically expect the money to bring 150 people off the streets and into permanent-supportive housing over the next 18 months.

Unfortunately, the city’s track record gives us little cause for optimism. A city audit in 2022 showed that Oakland spent $70 million on similar homelessness programs between 2019 and 2021, but the organizations that received the funds neglected to track outcomes to assess how effectively that money was spent.

What we do know is that, despite this spending, homelessness has continued to rise at alarming rates. Homelessness in California has grown by more than 50 percent since 2015, but in Oakland it has more than doubled over the same period. There are now over 5,000 homeless persons in the city on any given night, the majority of whom are unsheltered.

This reveals a vexing pattern: the more money we spend to alleviate homelessness, the worse the problem actually becomes. To unravel this mystery, we must look closely at the philosophy that has guided state and federal policy for the past decade.

Housing First—Core Principles

In 2013, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) adopted “Housing First” as its national homelessness policy, and California followed in 2016. This means that to receive state or federal homelessness grants, local agencies and non-profits have to comply with Housing First guidelines.

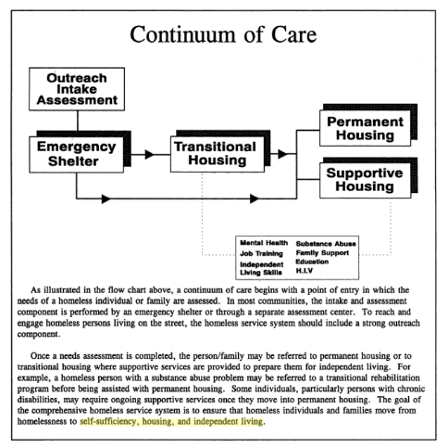

Housing First is built on a few principles. The first and most important is that to solve homelessness, we must provide immediate housing to people, without strings attached. This contrasts with the prior philosophy of residential treatment—variously known as “housing readiness,” “treatment first,” or the “continuum of care” approach to homelessness—which offered shelter for people while they participated in mandatory support programs, such as drug rehab, mental health treatment, and work training, among other things (usually tailored to the individual’s needs).

The second principle of Housing First is that tenant-selection is not decided on a “first-come-first-served” basis. The lion’s share of Housing First funds (72% of federal grants in California in 2022) is spent on Permanent-Supportive Housing (PSH), which prioritizes chronic and unsheltered homelessness—two separate but heavily overlapping categories of the homeless population. These categories also closely overlap with those who are suffering from a severe mental illness and/or untreated substance-use disorder.

The third important principle of Housing First is “harm reduction,” which in practice amounts to treating clients as lost causes, doomed to suffer from an incurable addiction until their death. California’s Housing First law explicitly mandates that “services are informed by a harm-reduction philosophy that recognizes drug and alcohol use and addiction as part of tenants’ lives.” An accompanying mandate of “non-judgmental communication” for how service providers must interact with clients is vague enough that even offering recovery services can mean that an organization forfeits its grants.

Promises vs. Results

The promise of Housing First, according to proponents, is that it leads to vastly higher rates of “housing stability” than programs that focus more on treatment and recovery. The original Housing First study, pioneered in the 1990s by clinical psychologist Sam Tsemberis, found that 88% of participants remained stably housed after five years, compared with only 47% of clients who participated in residential treatment programs.[1]

Taken at face value, these are impressive results, and they directly gave way to the extant practice of referring to Housing First as an “evidence-based” approach to homelessness. Unfortunately, the study also contained a number of caveats that have been ignored by overzealous Housing First policy advocates.

In the first place, it is worth noting that Tsemberis introduced “housing stability” as his measure of success, and in his program, this meant on-going housing subsidies. The clients he used as a control group, however, were in residential treatment programs that used a measure of success defined in 1994 by the Clinton administration: “self-sufficiency, housing, and independent living.”[2]

In other words, the clients with a lower success rate were expected to not only be “stably” housed, but also independent and self-sufficient. In Tsemberis’s own words, “the end point of this continuum is independent housing with few, if any, supports.”[3]While some people may believe that an 88% success rate for stable but subsidized housing may be preferable to 47% stable but unsubsidized housing, Tsemberis’s formula gives virtually no recognition to those people who are capable of becoming truly self-sufficient.

Under Housing First, even the 47% who would have been able to achieve that higher outcome remain permanently supported by taxpayers as PSH residents, which creates an ever-growing burden on homelessness budgets. They are no longer counted as “homeless” for official estimates, but their subsidies continue to draw from homelessness funds. This helps us understand why homelessness spending continuously increases.

Another important caveat in Tsemberis’s study is that he chose to focus exclusively on individuals who suffered from a severe, diagnosed mental illness. Essentially, this means that the outcomes his study discovered only meaningfully apply to those individuals who, fifty years ago, would have likely been permanently institutionalized. Although this constitutes a significant portion of the total homeless population, it is nonetheless a minority.

If half of the severely mentally ill population living on the streets was able to achieve independent housing stability, we might reasonably assume that the total homeless population would likely see even better results under a treatment-oriented program. Before Housing First became state and federal policy, it was possible to have alternative programs operating alongside each other, but now such alternatives are crowded out by the organizations that are propped up by billions of Housing First dollars.

This highlights one of the primary problems with Housing First as a policy, rather than an individual program. When the law mandates that organizations follow a certain approach, the government is effectively prescribing a one-size-fits-all solution for a social problem.

We can acknowledge that a certain segment of the homeless population will likely never be able to attain self-sufficiency, and Housing First may be the best way to humanely get them off the streets, but it is not humane to apply this assumption universally. California spent more than $100 million in FY 2022-2023 on permanent-supportive housing for homeless youth, which tacitly admits that California policy presumes that a homeless 17-year-old is destined to be a ward of the state for the rest of their lives. Does it really make sense to treat teenagers the same way we would an incurably mentally ill adult?

Finally, the harm-reduction component of Housing First is predicated on “platform theory,” which posits that permanent housing “is the platform from which people can continue to grow and thrive in their communities.” This precept is actually quite reasonable, except that its policy manifestation takes for granted that clients will pursue necessary treatment—particularly for substance abuse—through their own initiative. This is rarely realized in practice.

California’s unique approach to “harm reduction” actually makes it more difficult than other states to fund recovery programs because it prohibits any activity that might loosely be interpreted as “stigmatizing.” This has led to a pronounced shortage of treatment beds for people who genuinely do want help with mental illness or substance abuse. According to a report published last October by the Mental Health Advisory Board, “only 45 [crisis residential treatment] beds are available in Alameda County, which has a population of more than 1.6 million.”

On top of this, Housing First policy does not allow grant recipients to impose sobriety requirements on any of their housing units. This is highly problematic for people who are trying to break free from addiction because it means that they have no refuge from other users and dealers who would undermine their recovery efforts. The California legislature, at least, is currently considering a bill that would allow a portion of Housing First funds to go to recovery housing, but the prevailing policy is to warehouse all homeless persons in the same building, regardless of whether or not they use drugs or are trying to recover.

The result is that the people who do get into permanent-supportive housing face remarkably high rates of overdose death. Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, in fact, conducted a study on the overdose mortality rate among homeless New Yorkers, and they found that more than half of all drug-related deaths among people experiencing homelessness occurred in supportive housing or shelters. Tsemberis conducted his original experiment before fentanyl hit the streets, so he may be forgiven for not anticipating this uncommonly deadly drug. Now, however, we should question the wisdom and humanity of a homelessness strategy that values “housing stability” above the very lives of the people it purports to serve.

But for all these flaws in the Housing First philosophy, the simplest argument against California policy is that the homeless population has actually grown more rapidly since Housing First became official policy. Between 2007 (when HUD first began tracking the homeless population) and 2015, homelessness in California actually declined by nearly 17%, but since we adopted Housing First as state policy, homelessness has increased by almost 57% statewide. Unsheltered homelessness—the target demographic under Housing First—similarly fell by 18.5% between 2007 and 2015, but it has since jumped by an astonishing 67.5%.[4]

Clearly, the evidence stands in conflict with this “evidence-based” policy.