Until the onset of Covid-19, most public health experts explicitly rejected the use of large-scale quarantines, also known as lockdowns, as a viable policy response to a respiratory pandemic. Why then, within just a few weeks of the disease appearing in their countries, did those same officials—in the name of science and expertise—embrace draconian policies that shut down entire societies?

The judgment against lockdowns rested on the general failure of such measures in past pandemics. A 2006 study by the World Health Organization (WHO) concluded that lockdowns were “not demonstrably effective in urban areas” during the Spanish Flu outbreak of 1918. “Historical data clearly demonstrate that quarantine does not work unless it is absolutely rigid and complete,” observed John Barry, the author of a leading historical study of the Spanish Flu. His assessment relied on a US government comparison of 120 US military camps during the pandemic. The 99 camps that went into lockdown showed “no statistical difference” in controlling the outbreak when compared to the 21 that did not.

The lessons learned from this episode prevailed in the public health community for the next century. In March 2019, a WHO working group on pandemic influenza prepared a detailed analysis of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs), or policy measures that could be deployed in the event of a mass-outbreak. The report observed that “most of the currently available evidence on the effectiveness of quarantine on influenza control was drawn from simulation studies, which have a low strength of evidence.” They concluded that lockdowns of this type are “not recommended because there is no obvious rationale for this measure, and there would be considerable difficulties in implementing it.” The same report evaluated other NPIs such as contact tracing and social distancing, finding that the arguments for each were overly reliant on simulation modeling, which had “a very low quality of evidence.”

A September 2019 report on respiratory pandemic preparedness by the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security concurred, noting, “In the context of a high-impact respiratory pathogen, quarantine may be the least likely NPI to be effective in controlling the spread due to high transmissibility.” The same report further warned that “implementation of some NPIs, such as travel restrictions and quarantine, might be pursued for social or political purposes by political leaders, rather than pursued because of public health evidence” and called on the WHO to “rapidly and clearly articulate its opposition to inappropriate NPIs.”

No less than Anthony Fauci would go on record about the unwisdom of lockdowns, telling CNN on January 24, 2020, that they were “something that I don’t think we could possibly do in the United States, I can’t imagine shutting down New York or Los Angeles.” Fauci then reiterated his doubts in relation to lockdown measures being implemented in China at the time, “because historically when you shut things down it doesn’t have a major effect.”

In just six weeks’ time, nearly the entirety of the US public health profession, including Fauci, would jettison the previous century of scientific literature attesting to the ineffectiveness of lockdowns. Instead, they rushed to embrace the previously-deprecated approach of simulation modeling, and used it to place the majority of the world under mandatory quarantine. Five years later, we still have no clear answers for why this sudden, sharp reversal happened, let alone accountability for the public health officials who made the call to change course.

If any single event warrants credit for swaying the public health profession over to lockdowns, it is the publication of Report No. 9 by the epidemiology modeling team at Imperial College-London on March 16, 2020. The brainchild of Neil Ferguson, a computer scientist and physicist with no medical training, the Imperial College model forecasted catastrophic mortality figures in the coming months if the world’s leading economies did not go into immediate lockdown to contain Covid-19. The initial models projected 510,000 deaths in the UK and 2.2 million deaths in the United States by late July 2020 unless each country adopted a suite of NPI measures to shutter businesses and schools and restrict public gatherings. Ten days later, Ferguson’s team expanded their model to approximately 189 countries and other defined political boundaries. The expanded Imperial College report predicted similar levels of catastrophic death in almost every nation on earth, absent immediate measures to impose society-wide lockdowns.

It is difficult to overstate the significance of the Imperial College model in swaying public health officials to embrace lockdowns. The New York Times described it as the “report that jarred the U.S. and U.K. into action.” In Britain, Ferguson’s personal guidance induced Prime Minister Boris Johnson to reverse course on a previous voluntary distancing policy and embrace heavy-handed lockdowns. Led by Fauci and Deborah Birx, the US Covid task force issued its “15 days to slow the spread” guidelines on March 16, the day of the Imperial College model’s public release. This guidance and an accompanying declaration of a national coronavirus emergency effectively greenlit the governors of every state to impose lockdowns. Forty-three out of 50 governors followed suit in the days that followed.

Looking back upon this flurry of events, multiple clear warning signs pointed to the folly of the course that public health charted. The first is the selective deference to questionable expertise, which in turn took the form of a centrally planned pandemic response.

Neil Ferguson, dubbed “Professor Lockdown” in the press, saw himself elevated to an all-knowing sage of pandemic modeling whose careful scientific guidance to governments averted the very same astronomical death tolls that his models predicted. A simple Google search would have revealed that Ferguson was no disease-modeling Cassandra. Rather, his track record had more in common with a Y2K bug alarmist. Ferguson had a long history of publishing models with similar catastrophic projections for every public health scare of the past two decades. In the early 2000s, he hyped a Mad Cow Disease pandemic in Britain that would supposedly yield death rates in the hundreds of thousands. Then came a model for Mad Sheep Disease with similar tolls. Then, in 2009, a swine flu model predicted one-third of the earth would be infected in a matter of months. Over and over again, Ferguson’s previous models failed to pan out.

The Covid forecast from Imperial College Report No. 9 was no different from Ferguson’s previous alarmist projections, and peaking under the hood of this study revealed its fundamental shortcomings. Although it was touted to the world as the product of cutting-edge supercomputing, the “new” Covid model turned out to be a hasty and clunky adaptation of an earlier pandemic influenza simulation study that Ferguson and his team published in 2006. Its design employed a probabilistic agent-based simulation wherein estimated human contact rates in a fixed population were said to determine disease transmission. The resulting product had more in common with the “Sim City” video game of the late 1990s than an advanced supercomputer projection of Covid-19’s known characteristics.

Instead of any evidence-based grounding in the known characteristics of the Covid-19 virus, Ferguson’s model employed little more than crude, round-number guesstimations about how each NPI would allegedly reduce the probability of transmission. Their voluntary “home quarantine” parameter assumed a 75 percent reduction in community contacts, with 50 percent population compliance. Population-wide mandatory social distancing assumed a 75 percent reduction in outside contacts, offset by a 25 percent increase in at-home contacts. Home isolation of infected persons would reduce outside contacts by 75 percent, and so forth.

A further attestation of how poorly suited this model was to Covid may be seen in its original influenza application from 2006. Ferguson’s base model specifically excluded old age care homes, prisons, and healthcare facilities on account of being unable to approximate transmission rates in these locales. The first wave of Covid-19 hit especially hard in nursing homes, due to policy missteps in which government officials required the readmission of infected patients to these facilities out of the belief that it could alleviate feared strains on hospital capacity. In reality, convalescing Covid patients ended up introducing the virus into otherwise-closed nursing home facilities where it spread among staff and other residents. The Imperial College model, it turns out, neglected to account for the single greatest vulnerability for Covid-19 transmission, while focusing its modeling on a guesstimated reduction in contacts among the general population.

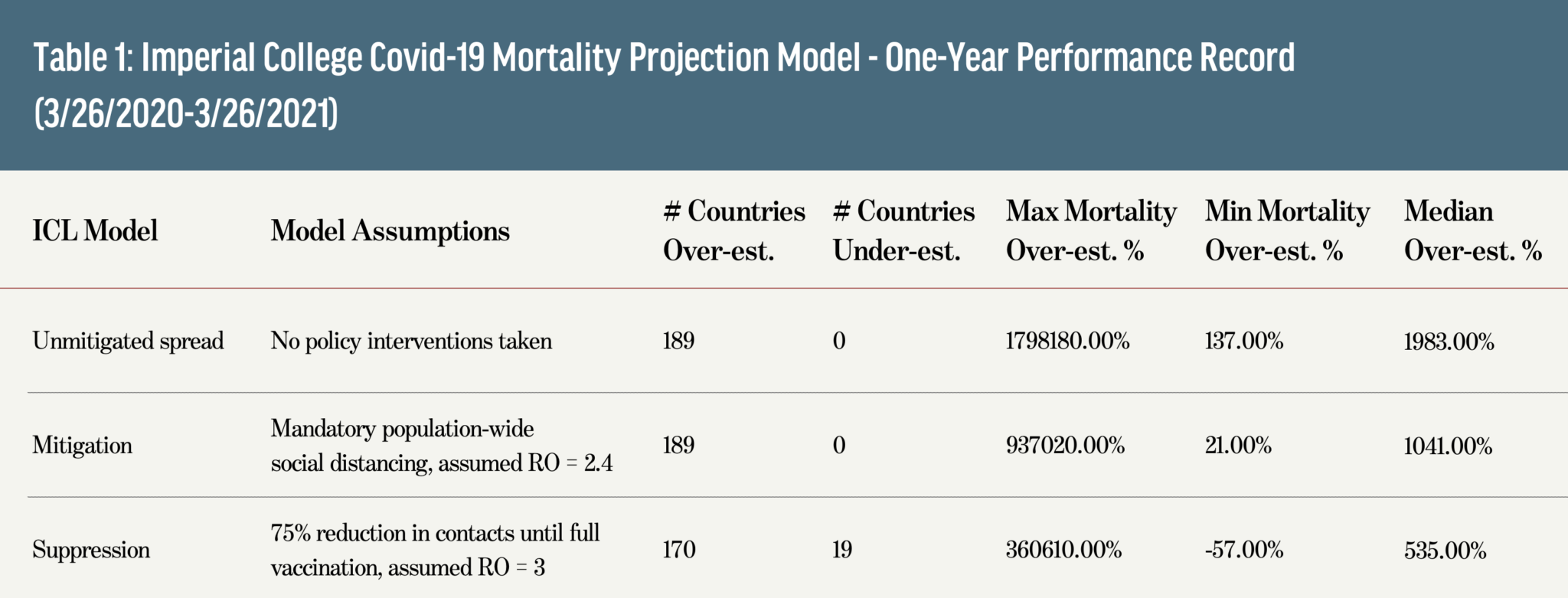

The track record of Ferguson’s centrally planned pandemic response model reveals its abject failure in nearly every single country on earth. Table 1 below shows the 1-year performance rate of mortality projections the three main modeled scenarios: an “unmitigated spread” model where no policy interventions are taken, a “mitigation” model that employed mandatory social distancing-style lockdowns, and a “suppression” model that involved a mandatory society-wide reduction of contacts by 75 percent, held in place until the population was fully vaccinated (this last heavy-handed approach resembled the “CovidZero” efforts eventually employed in China and a few other totalitarian states). No country reached the death tolls that Ferguson’s team projected in the first two models, and only 19 exceeded the tolls predicted by the “suppression” model, even though few locales employed its associated policies.

Despite the many readily-observable deficiencies of the Imperial College model, public health authorities continued to embrace its prescriptions for another year of recurring lockdowns. This path dependency is even more alarming, given that the predictive failures of Ferguson’s team were already apparent by the summer of 2020.

Sweden stands apart during Covid-19 for bucking the lockdown measures adopted in almost all other developed economies. Instead, Swedish health authorities adopted a policy of voluntary general health and sanitation guidance while also keeping most schools and businesses open for the duration of the pandemic. According to the Imperial College team’s international forecast from March 26, 2020, Sweden’s approach should have yielded an unmitigated spread with between 66,000 and 90,000 deaths in the country by late summer 2020. Even with mandatory social distancing measures, the Imperial model projected that Sweden would hit between 30,000 and 42,000 deaths in this same period. As of August 31, 2020, Sweden had recorded just a fraction of these totals at just 5,800 Covid deaths. Clearly, something was badly amiss in the parameters and probability assumptions of Ferguson’s model.

The emerging data from Sweden did little to sway the use of lockdowns though, which soon morphed into a political cause. When confronted with these data, Ferguson’s team falsely claimed on their Twitter feed that they had never produced a model for Sweden (their data file with numbers for Sweden and every other country remains on the Imperial College website to this day). The subsequent literature on lockdown efficacy has continued to tout the effectiveness of this policy, however, it uses inappropriate empirical designs to do so. The most heavily cited pro-lockdown study from the Covid era, for example, purports to estimate the number of “lives saved” by using its own simulation model as a counterfactual test against observed mortality statistics, despite having never validated the accuracy of that simulation.

When simulation studies of this type are excluded on account of their inappropriate causal inference designs, the evidence in support of lockdowns disappears. A sweeping literature review and meta-analysis of studies using actual data accordingly came to damning conclusion about the world’s experiment with these policies during Covid-19: “Lockdowns in the spring of 2020 had little to no effect on COVID-19 mortality.” The anti-lockdown consensus of the public health literature prior to March 2020 was once again vindicated, albeit at astronomical costs, from the embrace of simulation modeling and its unfounded prescriptions during Covid.

So why did public health fail to course-correct during Covid amid mounting evidence that lockdowns were not working as claimed? Allow me to suggest an answer rooted in public choice economics and a prescient observation from centuries past. In times of crisis, the public often demands action with little regard for its efficacy. Public officials, in turn, are happy to oblige in the furtherance of their own authority, prestige, and allocations from the public treasury.

Herbert Spencer noticed this exact pattern during an earlier epidemic, the deadly cholera outbreaks in mid-nineteenth century London. Writing in his classic Social Statics (1851), Spencer commented upon the alignment of incentives between the public’s demand for action and the politically-invested sectors of public health to supply it:

Citizens look grave and determine to petition parliament about it. Parliament promises to consider the matter; and after the usual amount of debate, says—Let there be a Board of Health. Whereupon petitioners rub their hands, and look out for great things. They have unbounded simplicity—these good citizens. Legislation may disappoint them fifty times running, without at all shaking their faith in its efficiency.

Some 170 years later, we are still captives of the same forces. When the public sphere weds itself to a specific course of action, dismissing its failures as sunk costs and continuing to prop up the many Fergusons and Faucis who claim public credit for the initiative of action itself, the processes of scientific testing and scrutiny can little-endure. A century of knowledge is thus set aside for the fashionable and flashy promise of a plan, asking not whether its imagined design will ever work.