The anniversary of Malcolm X’s birth brings to mind the parallels to another great African-American activist: T.R.M. Howard. The two came to know each other late in Malcolm’s life, often talking late into the night at Howard’s home. In 1965 Howard gave the main eulogy for Malcolm at a memorial service in Chicago and headed the Chicago fund to raise money for the education of his children.

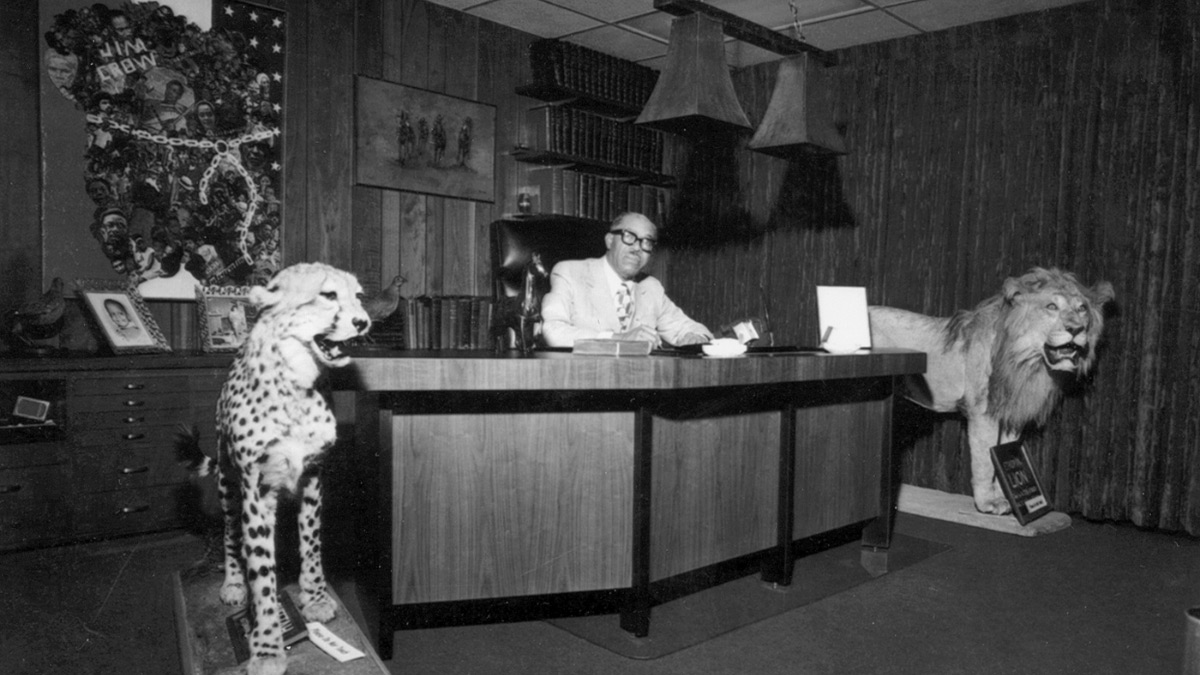

Although each grew up in poverty and were raised in great part by single mothers, their paths soon radically diverged. Howard, after getting a medical degree with the help of a white doctor, became the chief surgeon of the Taborian Hospital in the all-black town of Mound Bayou, Mississippi, where he provided affordable and high-quality health care to thousands. In addition to owning a 1,000-acre farm, he established an insurance company, a home-construction firm, and even a small zoo.

During the early 1950s, Howard led the largest civil-rights movement in Mississippi and organized a successful boycott of service stations that refused to provide restrooms for blacks. He later played a pivotal role in the Emmett Till murder case. He helped to find witnesses to testify against the white killers and provided an armed escort to the trial for Till’s mother. Howard moved to Chicago in 1958, where he mounted an unsuccessful campaign for Congress (as a Republican) and opened the city’s largest privately owned black medical center.

Compared to Howard, Malcolm’s initial career path was much less promising. He dropped out of junior high after a teacher brushed aside his ambition to be a lawyer. He became a house burglar, which was followed by a long stint in prison where he converted to the Nation of Islam, a black-separatist organization under Elijah Muhammad that taught that whites were a “devil race.” After his release Malcolm gained some national renown as the Nation’s chief minister, but he eventually broke from that organization, though he remained a Muslim, and rejected the Nation’s racism. His ideas were still developing when, at the age of 39, three men affiliated with the Nation of Islam assassinated him.

Malcolm and Howard had similarities in style and often thought alike. Their speeches showed the common touch, perhaps nurtured by memories of childhood deprivation, and were peppered with “down home” rhetoric that connected with audiences. They hammered on the need for African-Americans to go into business as a necessary first step toward mastering their own fate. Howard proclaimed that “in this industrial age, thrift, industry and business efficiency must become an integral part of the Negro’s religion,” while Malcolm stressed that “the black man himself has to be made aware of the importance of going into business.” Malcolm reminded audiences that although Woolworth had started as a mere “dime store,” it had eventually flourished.

Howard and Malcolm differed somewhat from Martin Luther King Jr. in highlighting the importance of armed self-defense. Malcolm cited the Second Amendment as justification to form rifle clubs to deter racist attacks, while Howard found clever ways to evade restrictions in Mississippi that prevented blacks from carrying concealed pistols. Howard’s arsenal included an array of weapons, including a Thompson submachine gun. One reason whites never attacked his civil-rights rallies, which sometimes drew crowds of 10,000, was that they knew that many participants were armed and prepared to shoot back.

Howard agreed with King that nonviolence was the best approach to striking down Jim Crow laws and disfranchisement. So did Malcolm, more or less, in his later years. Both, however, remained skeptical of what they regarded as King’s overemphasis on political strategies and goals. Much more than he, they touted economic self-help as an essential condition for political success and underlined the need for the oppressed to, if necessary, arm as a means to deter violent attacks or threats of violence.