Last month’s arrest of two black men at a Philadelphia Starbucks has amplified accusations of a double standard in American society. Along with a financial settlement with the men, Starbucks responded by promising to close its stores for part of May 29 in order to conduct racial-bias training for store employees.

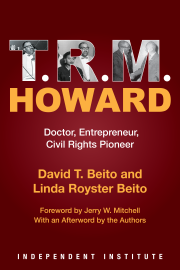

That’s one way to address discrimination. But there are others as well, as T.R.M. Howard and his Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL) demonstrated in a far more hostile setting: segregated Mississippi in the early 1950s.

Although Howard was one of the wealthiest blacks in Mississippi, he navigated in perhaps the worst of all racial environments. When Howard spoke at the RCNL’s first meeting in 1951 his audience knew exactly what he meant: “You have to be black man in Mississippi at least 24 hours to understand what it means to be a Negro in Mississippi.” The indignities ran the gamut from the degrading (a black man being called “boy,” a black woman, “mammy”) to the fatal. A white killer of a black almost never faced punishment.

Founded in 1951, the RCNL immediately set out to chip away at this system of repression. Howard’s capable assistant was future civil rights legend Medgar Evers, an employee of Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Co., one of the many black businesses Howard began.

In 1952, the RCNL launched an ambitious boycott of gas stations that refused to provide restrooms for blacks. It distributed an estimated 50,000 bumper stickers with the slogan “Don’t Buy Gas Where You Can’t Use the Rest Room.” The RCNL had picked its target well. Blacks wielded some economic leverage with gas stations because, as Howard pointed out, they were nearly as likely as whites to own cars. A typical scenario during the boycott was for a black customer to pull up to the gas pump, ask to use the restroom, and then drive off if the answer was no. All available accounts testify to the boycott’s success as many service stations started to install restrooms, in part, because national chains put pressure on them.

When the RCNL petitioned school districts to implement the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, it faced its greatest challenge yet. Members of the white Citizens’ Councils struck back by systematically refusing loans and other credit to activists. In a stroke of genius, Howard organized a nationwide effort to persuade black organizations and businesses to transfer their deposits to the black-owned Tri-State Bank of Memphis, on whose board he served. Tri-State, in turn, loaned the money to victims of the Citizens’ Council “credit freeze” at market rates.

By 1955, Howard and his associates (dubbed the “anti-freeze boys” by The Chicago Defender) had helped transfer nearly $300,000 in deposits to Tri-State. This new source for non-discriminatory loans saved many from economic ruin.

Howard’s challenge to the abuses of the Jim Crow era was not just reactive. He always regarded more black business and home ownership as the best means to throttle discrimination. An intended byproduct of the restroom boycott was to spur patronage for black-owned gas stations, including one run by RCNL officer Amzie Moore in Cleveland, Mississippi. Howard also opened a black-owned hospital that gave affordable medical care on the cooperative plan without a penny of governmental aid.

Today, those who want to advance racial justice and economic advancement can learn much from those, such as Howard, who fought back 70 years ago.

Two key lessons still apply: first, the need to tailor responses to particular situations; and, second, the necessity to always look for ways to build clout by establishing businesses or other economic foundations.

While the Starbucks episode shows that bias and unequal treatment still remain, business, Howard demonstrated, should be part of the solution, not part of the problem.