Overview

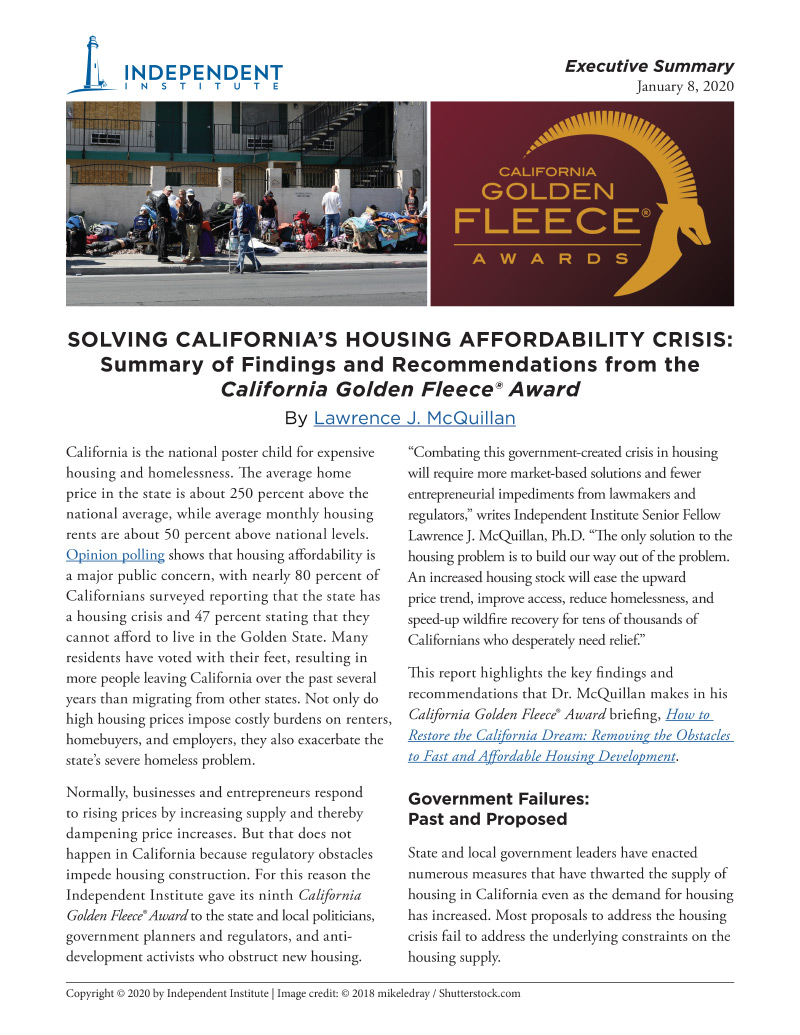

California is the national poster child for expensive housing and homelessness. The average home price in the state is about 250 percent above the national average, while average monthly housing rents are about 50 percent above national levels. Opinion polling shows that housing affordability is a major public concern, with nearly 80 percent of Californians surveyed reporting that the state has a housing crisis and 47 percent stating that they cannot afford to live in the Golden State. Many residents have voted with their feet, resulting in more people leaving California over the past several years than migrating from other states. Not only do high housing prices impose costly burdens on renters, homebuyers, and employers, they also exacerbate the state’s severe homeless problem.

Normally, businesses and entrepreneurs respond to rising prices by increasing supply and thereby dampening price increases. But that does not happen in California because regulatory obstacles impede housing construction. For this reason the Independent Institute gave its ninth California Golden Fleece® Award to the state and local politicians, government planners and regulators, and anti-development activists who obstruct new housing.

“Combating this government-created crisis in housing will require more market-based solutions and fewer entrepreneurial impediments from lawmakers and regulators,” writes Independent Institute Senior Fellow Lawrence J. McQuillan, Ph.D. “The only solution to the housing problem is to build our way out of the problem. An increased housing stock will ease the upward price trend, improve access, reduce homelessness, and speed-up wildfire recovery for tens of thousands of Californians who desperately need relief.”

Government Failures: Past and Proposed

State and local government leaders have enacted numerous measures that have thwarted the supply of housing in California even as the demand for housing has increased. Most proposals to address the housing crisis fail to address the underlying constraints on the housing supply.

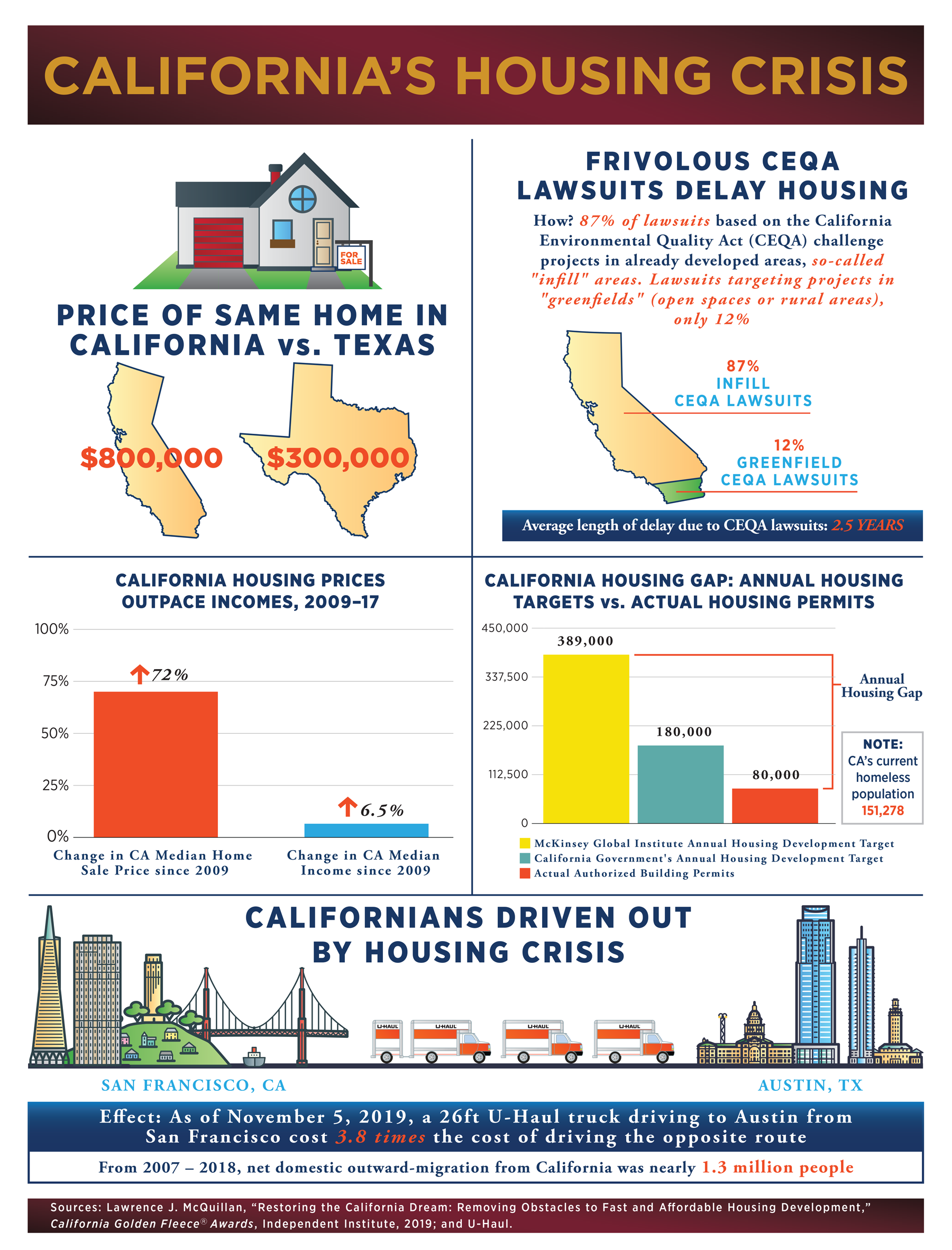

High Costs of Regulation. The fundamental cause of high housing prices in California is the significant costs imposed by numerous state and local housing regulations. Nationwide, the full panoply of regulations amount on average to about one-third of the total cost of building housing. Those costs—which translate into tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars—are higher in California, which National Association of Home Builders chairman Granger MacDonald calls “the most heavily regulated state in the country.”

The costs of restrictive zoning, permitting, and other regulatory barriers are inevitably passed along to homebuyers and renters, and reduce the supply of housing and drive up its cost. A study of land-use regulations and the California housing market from economists at the University of California, Berkeley, found that the degree of regulatory stringency was positively associated with higher house prices and residential rents. It also found that new housing construction rates were lower in more heavily regulated cities than in less regulated cities. These conclusions are consistent with earlier research showing the cumulative effects of such regulations on housing prices elsewhere in the United States.

In Los Angeles, restrictive zoning laws have been a major impediment to certain types of new housing. The city currently bans any housing other than detached single-family homes on about 75 percent of its residential land. Whereas in 1960 Los Angeles was zoned for up to 10 million people, by 1990 the city “had downzoned to a capacity of about 3.9 million, a number that is only slightly higher today,” reports the New York Times.

PLAs and Prevailing Wages. For some development projects, the costs have been artificially raised through the use of project labor agreements (PLAs), which mandate the use of more expensive union labor or the use of government-determined “prevailing” (i.e., union) wage rates. Prevailing-wage mandates increased average construction costs for affordable housing projects by between 10 percent and 25 percent, according to a May 2017 report from the California Center for Jobs and the Economy and the California Business Roundtable. In areas such as Los Angeles, PLAs could hike market-rate housing prices by as much as 46 percent. This finding is consistent with other studies that have found that PLAs could increase both bid and construction costs by up to 20 percent.

Despite the added costs, PLAs are common because they benefit politically connected and powerful labor unions that can deliver votes and campaign contributions to politicians.

NIMBYism. Homeowner and tenant groups are frequent opponents of new housing construction in their neighborhoods. Groups in wealthy, high-density cities such as San Francisco and Los Angeles have provided loud opposition to recent upzoning legislation proposed in the state legislature, and their elected representatives have listened. Activists colloquially known as NIMBYs (“Not in My Backyard”) publicly justified their antagonism to new housing as necessary to preserve local character or local control, but the effect is to keep people out by keeping housing scarce and inaccessible.

Faux Environmental Lawsuits. Anti-housing obstructionism in the state often wears pro-environment disguises. Groups opposed to new housing developments or homeless shelters have invoked the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) to slow or stop construction projects ever since its enactment in 1970. CEQA requires state and local governments to consider and mitigate the impacts of development projects on the environment, including (as the result of later amendments) impacts on line-of-sight views and traffic patterns. The law also requires local governments to hear CEQA-based appeals against projects, which are often grounds for court challenges that can drag out for years. As few as one person or one vocal interest group can delay or stop a project through court action.

Business rivals and environmental activists use CEQA to thwart development projects, although seldom for the sake of environmental protection. A 2015 study by law firm Holland & Knight found that only 13 percent of CEQA lawsuits in Southern California were filed by established environmental organizations, and 80 percent of such lawsuits concerned development in “infill” areas surrounded by existing development, not “greenfields,” the open space or rural areas more likely to be affected by new building. A follow-up study in 2017 found that of the 14,000 housing units that had CEQA-based challenges, 98 percent of the challenged units were located in existing community infill locations and 70 percent were located within one-half mile of transit services. The state Legislative Analyst’s Office has concluded that CEQA appeals delay a project by an average of two and a half years. Some delays are much longer.

Bureaucratic Redevelopment Subsidies. One approach favored by some elected officials is to make taxpayer-funded financial resources available for local development. Senate Bill 5 adopts this strategy. If enacted, SB 5 would establish a committee to award funds on state-approved redevelopment plans, which include affordable housing, transit-oriented development, infill development, and revitalizing and restoring neighborhoods. Despite its seeming attention to details, SB 5 is riddled with tedious, top-down, command-and-control directives that will not solve the housing problem, assuming any homes actually get built through the program.

Downvoting Upzoning. Another approach has been to favor “upzoning” or re-zoning certain areas to allow construction of multifamily housing, such as apartment buildings, condominiums, townhomes, and single-resident occupancies (SROs). Until now, however, such efforts, including Senate Bill 827 and SB 50, have suffered defeat in the California State Legislature. This is especially disheartening because, as a study by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation notes, higher-density housing “enable[s] more units to fit onto scarce land.”

Passing the Buck(s) on Homelessness. Governor Gavin Newsom signed a fiscal year 2019-2020 state budget that authorizes a historic $1 billion in new aid to California cities fighting homelessness, including $650 million in emergency sheltering and $120 million for programs that coordinate housing. However, similar aid provided in 2018 by then-Gov. Jerry Brown did not prevent the surge in homelessness. It remains to be seen whether Gov. Newsom’s task force of 13 “regional leaders and statewide experts”—primarily politicians—will offer valuable advice on how his administration can best spend the $1 billion to combat homelessness, but years of disappointment warrant continued skepticism.

In San Francisco, where homelessness has reached crisis levels, Mayor London Breed led the fight for passage of a $600 million affordable-housing bond measure on the November 2019 ballot—the largest housing bond in city history—to potentially fund 2,800 units. Voters approved the bond measure, Proposition A, in November 2019. City officials have also advanced plans to build new housing to shelter a portion of the homeless population. Local opposition, however, threatens to delay or block these new construction plans through expensive litigation.

In Los Angeles, voters approved a $1.2 billion bond measure (Proposition HHH) in 2016 and a sales tax increase (Measure H) in 2017 to build 1,000 new housing units each year over the next decade. However, various delays and setbacks quickly arose, with delays averaging 203 days. As of July 2019, none of the new housing units had been completed and only 239 were projected to be completed by year’s end, if all went according to plan. Such delays are emblematic of government projects. Construction under Los Angeles’s Proposition HHH is subject to government-mandated PLA.

Rebuilding after Wildfires. Fixing California’s housing crisis became particularly urgent after the record wildfires of 2017 and 2018. The city of Paradise (Butte County) is a tragic case in point.

Approximately 90 percent of its residences were destroyed by the 2018 Camp Fire, sending nearly 20,000 people to relocate to Chico. Overnight, every hotel and guest room became occupied. Hundreds of people had to live out of their cars, RVs, or in emergency shelters throughout the city. Children displaced by the fire attended school in makeshift classrooms at a local hardware store.

Officials in Paradise have warned residents that rebuilding their town will be a prolonged process and residents of Chico have nearly lost all hope of a return to normalcy. Their fatalism may be understandable, given an ever-changing landscape of housing regulations and government-mandated paperwork.

Despite their handwringing over California’s housing-affordability crisis, many politicians are unwittingly doing everything they can to raise home prices by artificially restricting supply, thus reducing access to affordable housing. But this problem can be reversed.

Recommendations

Improving California’s housing market will require addressing both the myriad burdensome regulations and defeating the hostile special interests whose priorities are out of sync with those seeking affordable housing options, especially low-income people. Here are the most promising steps for moving forward.

- Deregulate zoning and land-use restrictions, especially those that impede multi-family apartment buildings. For the average California city, adding a new land-use regulation reduces the housing stock by about 40 units per year, one study found.

- Streamline building-permit approvals to speed up construction and reduce costs. In many parts of the country, a developer can build multiple projects in the time it takes to permit and build one project in California.

- Abolish the California Environmental Quality Act. CEQA, which no longer serves its original purpose, may be the biggest impediment to residential housing development in the state. If abolishment is not an immediate option, allowing infill developments to proceed without CEQA reviews would be a reasonable reform.

- Eliminate unnecessary state building codes and transfer authority to local governments. The solar panel mandate, which goes into effect January 1, 2020, is the latest example of costly state regulation. Some estimate that it will raise new home prices by $10,000 to $30,000.

- Eliminate expensive development impact fees. Local fees average more than $22,000 per single-family home, about three-and-a-half times the national average of $6,000, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office. Cities should eliminate impact fees and use private provision of services.

- Eliminate rent controls and “affordable housing” mandates, which discourage housing by making it less profitable. Such measures act like a tax on developers, property owners, and market-rate homebuyers, thereby decreasing housing availability.

- Eliminate pro-union regulations that drive up the cost of labor. Project labor agreements and “prevailing wage” legislation undercuts freedom of contract and increases construction costs in California.

- Encourage entrepreneurial innovation. Entrepreneurs would provide fast and affordable housing if only they could enter markets, compete, and build units at the price points demanded by consumers. Examples of quick, inexpensive, and increasingly high-quality housing include modular or “prefabricated” homes, so-called “tiny homes,” and futuristic 3D-printed homes, which in some cases can be built in 24 hours for as little as $5,000.

- Make building housing a constitutional right. The quickest exit from the regulatory thicket might be to amend the California Constitution to establish an individual right to build residential housing. Then if housing opponents wished to alter or end a development project, they could do so only through the voluntary agreement of builders.

- Empower neighborhood associations to contract with developers. Under the current approach in California, established residents incur zero cost for voting against, or otherwise opposing, a housing project. To end the bias against development, private “neighborhood associations” could be established to negotiate with developers, requiring direct compensation of members for any negative spillover effects.

The only way to solve the housing crisis is to allow housing entrepreneurs to build. It is incumbent on state and local officials to avoid the temptation to overregulate the housing market and to get out of the way.