As Americans mark the 228th anniversary of the signing of the American Declaration of Independence this Fourth of July, two parallels between our Revolution and today’s insurgency in Iraq come to mind. One, based in myth, would lead its advocates to folly, while the other deserves serious consideration.

The mythical parallel, drawn by intellectuals as diverse as Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg and Iraq war-hawk, neo-conservative godfather Irving Kristol is what might be called “The Minority Myth.” Cited in numerous books about the Revolution is a letter written by founding father John Adams which seems to indicate that only one third of the American colonists were for the Revolution, another third were against it, and a final third were neutral or indifferent to the whole affair. The letter has been brought into favor by certain parties hoping Iraq turns to democracy, for, if true, this claim would suggest that the current lack of consensus on democracy in Iraq does not foretell defeat of the efforts to impose it there.

Yet a close reading of Adams’s letter indicates precisely the opposite interpretation. Adams’ “well-known” letter was dated January, 1813. Written so many years after the American Revolution, it becomes clear that Adams was actually discussing American opinion about England and the French Revolution during his presidency, 1797-1801: “The middle third, composed principally of the yeomanry, the soundest part of the nation, and always averse to war, were rather lukewarm both to England and France. . . .”

That the Revolution was in fact popular among a majority of Americans is apparent from the actual turn of events. Americans were overwhelmingly opposed to the Stamp Act of 1765. However, it is unlikely that that crisis alone would have motivated a majority to support the Revolution had it not been for a later event characterized by the great contemporary American historian Mercy Otis Warren as a day that would “live in infamy” (a phrase Franklin D. Roosevelt and his speechwriters expropriated for themselves on December 8, 1941): when the British sent an army from Halifax to occupy Boston in October, 1768. This was an affront to the Standing Army Act, and, the Americans thought, to the British Constitution itself.

The violence of the British occupation led to the Boston Massacre in 1770, the Boston Tea Party in 1773, and the Intolerable Acts a year later, resulting in a “loss of legitimacy” for the British government in the minds of the majority of the Americans. And it was this loss of legitimacy that ultimately lost the British the war. While some British policymakers hoped that the end of American protests indicated a victory, the Americans were in fact busy supplying the closed port of Boston from Salem, and militias were now conducting drills in the towns and villages above Boston. In fact, both times British armies ventured into the interior, on the assumption that there were large numbers of Loyalists there who would support the King’s cause, they instead experienced ruinous defeats.

The lessons of the American Revolution applicable to today epitomize the adage, “those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it.” Such a sea-change has occurred in Iraq, as continued American occupation and misuse of power has resulted in increasing numbers of common Iraqis seeing America’s involvement—and America’s hand-picked replacement government—as illegitimate.

The second parallel to draw between the American Revolution and Iraq today is the power of the militia. For despite the popular picture of George Washington and his forces, it was ultimately the popular militia that truly defeated the organized British army. The British left New England early in the War, and controlled really only New York City for the duration. They evacuated Philadelphia due to American pressure. British soldiers did not go out at night in less than battalion strength.

Americans in Iraq are similarly hunkered down and facing a hostile and armed populace. Even for well-equipped armies, confrontation inevitably means killing many among the civilian population who sustain these unconventional forces. And the vicious cycle is that such violence only reinforces the “loss of legitimacy” that feeds continued insurgence. The first rule of counterinsurgency is to separate the guerrilla or irregular forces from the general population. This implies the occupiers have control, in some sense, of the entire country. And such is far from the case in Iraq.

In America, the conflict with the British played out from 1768 to1783, and it took until 1789 to craft a Constitution that could be agreed upon. The sooner the Iraqis can start their own Constitutional Convention, forging a system that is truly “of and for” their people, one with “legitimacy” and capable of gaining the consent of the governed, the sooner insurgency, death, and destruction will end in Iraq.

The American Revolution and Iraq

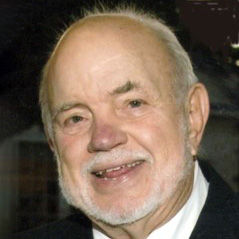

William F. Marina (1936–2009) was a Research Fellow at the Independent Institute and Professor Emeritus in History at Florida Atlantic University.

Comments

Before posting, please read our Comment Policy.