In a provocative essay for the Chronicle of Higher Education, literature scholar Michael Clune calls attention to an alarming trend in academia: “Starting around 2014, many disciplines—including my own, English—changed their mission” away from traditional scholarship and “began to reframe their work as a kind of political activism.” Clune is not alone in observing this shift, which some have dubbed the “Great Awokening” as a reflection of its connection to a peculiar brand of hard-left politics that came to dominate scholarly discussions in this period. Sociologist Musa Al-Gharbi’s book We Have Never Been Woke associates this event with a shift in language among intellectual elites who pay symbolic homage to “social justice” causes as a way of elevating their own status as elites.

After a decade of woke discourse, the activist turn has taken a reputational toll on elite institutions. Over this same period, public confidence in higher education plummeted across almost all groups. Trust in the traditional news media hit record lows, with much perceptions of political bias driving the decline. At the same time, a growing body of evidence suggests that training in the activist framework of “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” (DEI) actually increases social animosity and resentment.

At the same time, universities and journalists have largely shirked any retrospection for their predicament, preferring instead to blame “uneducated voters,” “right wing misinformation,” and Trumpism for their diminishing credibility. One common narrative on the left attributes the anti-woke backlash to an orchestrated disinformation campaign from their adversaries on the right. A widely-touted article in the New Yorker accused conservative commentator Christopher Rufo of “inventing” a moral panic over Critical Race Theory (CRT) in the early 2020s by “weaponizing” an obscure and largely innocuous set of concepts from advanced law school seminars. MSNBC picked up the claim and alleged a full-fledged conspiracy was afoot to discredit higher education. A Guardian columnist accused the right of waging a manufactured “war on wokeness.” Elite academics such as Harvard’s Naomi Oreskes insisted that the leftward political shift on campus is a carefully cultivated right wing myth.

In each case, these commentators have their timelines exactly backward. Not only is the “Great Awokening” of the early 2010s real, it is strongly attested in empirical evidence around shifting language norms. Proprietary jargon terms have long been a domain of the campus left, and particularly an epistemic framework known as “critical theory.” In most of the humanities and many social sciences, critical theory is all the rage at the moment. This school of thought initially emerged as outgrowth of Marxist philosophy on the periphery of the mid twentieth century academic left, particularly as they grappled with the failure of revolutionary Marxism to materialize and the discrediting atrocities of the Soviet Union. Critical theorists posit that the “traditional theory” framework of evidence-based descriptive analysis is more or less a veneer for propping up the power structures of a ruling capitalist system. The critical theorist’s self-appointed task, then, is to “liberate” the oppressed through radical activism and an equally radical pedagogy, aimed at tearing down the same power structures they purport to have identified.

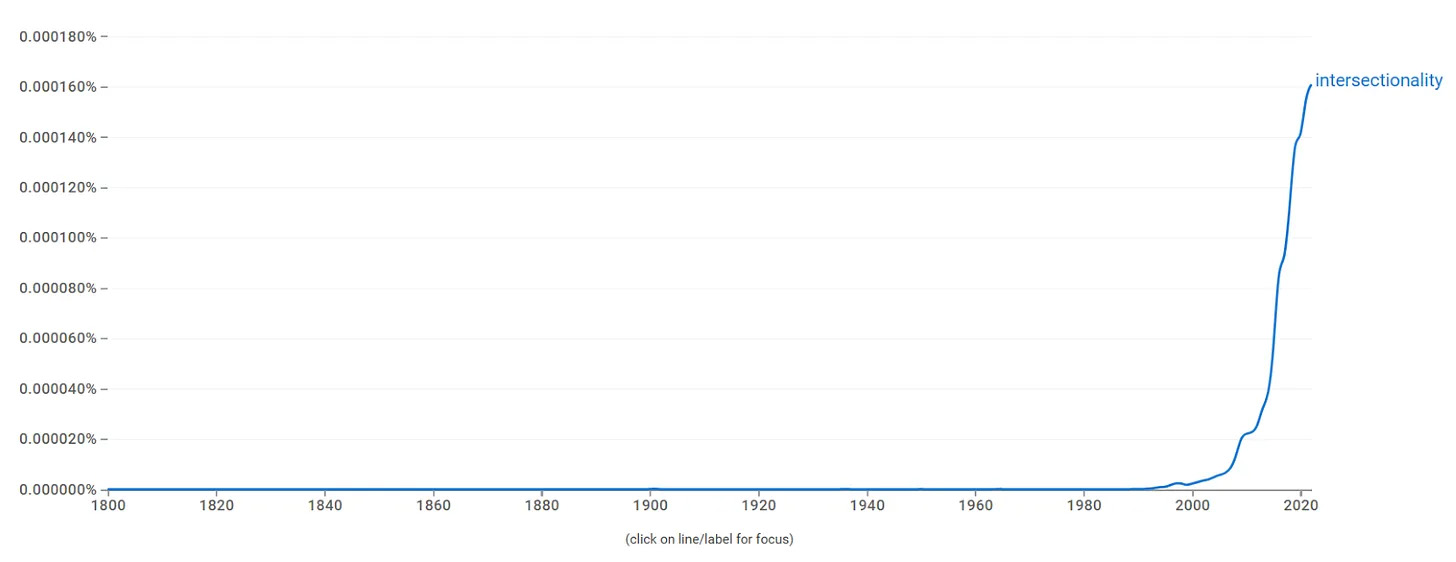

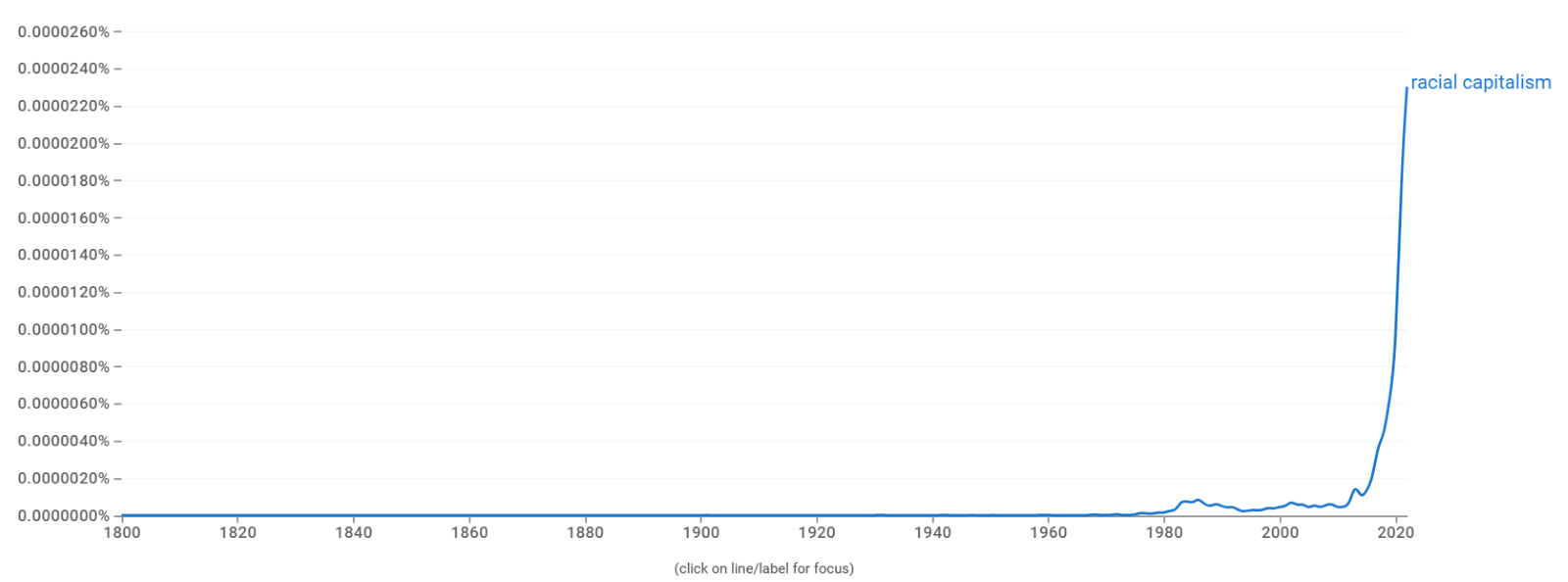

Google’s Ngram database, which measures the appearances of words, names, and phrases over time as a percentage of published works in the Google Books corpus, offers a powerful visualization of how critical theory terminology shifted from the academic periphery to the mainstream at a shocking pace between roughly 2012 and 2016. Notably, the evidence it reveals about the “Great Awokening” predates the most frequently cited defenses from the academic left: the first election of Donald Trump in 2016 and Rufo’s alleged creation of a moral panic around CRT, beginning in 2020.

Take, for example, the term “intersectionality.” A core concept of the CRT subfield, intersectional analysis purports to analyze how power structures operate across identity groups and particularly in situations where a person belongs to more than one overlapping identity. Critical theorists then use this framing as a basis to indict capitalism, liberal political philosophy, and legal-constitutional theories premised on equal treatment under the law, among other things, as purveyors of oppression. The term is of relatively recent origin, having first appeared in a 1989 article by CRT co-founder Kimberle Williams Crenshaw. And for the first two decades of its use, only the far-left periphery of academia even noticed. Between 2012-2016 Ngram usage of the term skyrocketed, producing a hockey stick-like graph that continues to the present day.

Intersectionality is not alone in exhibiting this pattern. A similar hockey stick trend may be seen for the term “racial capitalism,” which attempts to reduce the entirety of free-market capitalism to the extractive exploitation of racial minorities. The term originated on the extreme fringes of left wing academia, first appearing in a 1983 book by Marxist political theorist Cedric J. Robinson. Like intersectionality, “racial capitalism” was mostly ignored for its first few decades of life. Its Ngram hockey stick shows an exact turning point in 2014, after which its use becomes ubiquitous.

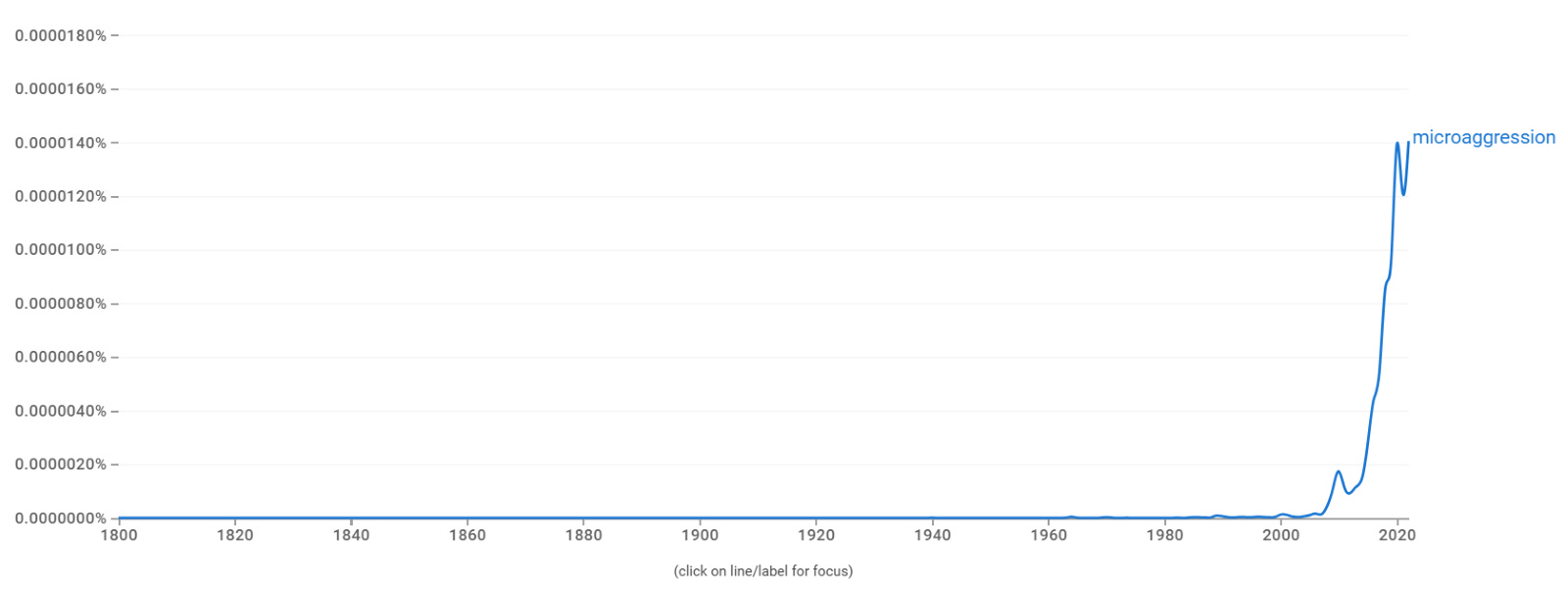

Numerous other proprietary jargon terms from “woke” academia follow the same pattern. The concept of “microaggression” traces back to the early 1970s work of psychiatrist Chester M. Pierce, although it initially saw little use outside of a few academic journal references. It became a cornerstone of the emerging DEI industry in the late 2000s, then burst into the mainstream with another hockey stick pattern. Once again, the timing of the discrete spike is in 2013-2014.

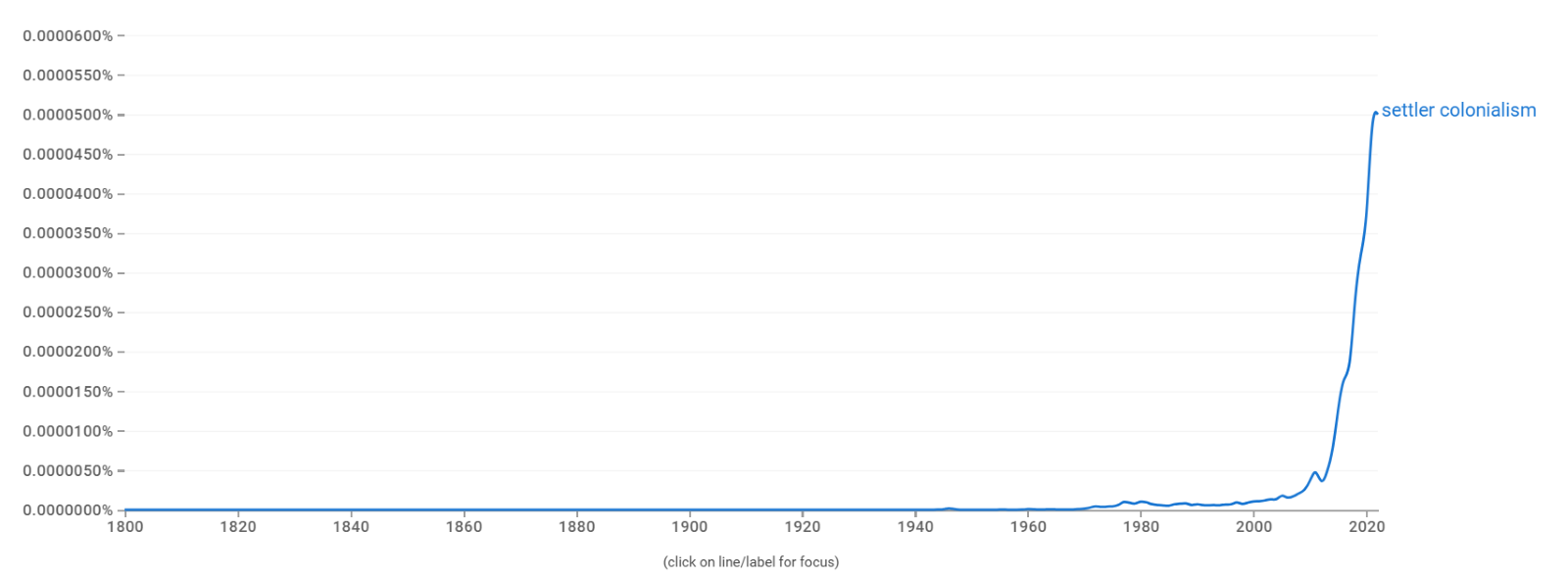

The same pattern appears for dozens of other jargon terms and phrases from the academic far-left. The concept of “settler colonialism” lingered in obscurity for decades until undergoing a hockey stick spike that started between 2013-2015.

The term “Global South,” a geographic designator from postcolonial theory, initially saw only tepid adoption on the academic far-left. After a decade or so of slightly rising use, its hockey stick takes off around 2012-2014 in a discrete spike that persists to the present.

An even more revealing pattern appears around the term “Latinx,” a neologism that purports to offer a gender-neutral alternative to the Spanish language designators Latino/Latina. Although the term has almost no adoption in the Spanish-speaking world, it has become the favored word of the English-speaking academic and journalist left when describing persons from Latin cultures and ethnicities. English use of “Latinx” essentially sprung from nowhere in 2014, followed by a familiar hockey stick rise. English Ngrams for Latinx even overtook the longstanding feminine designator “Latina” in 2020, and are rapidly converging on the masculine “Latino.”

The concept of Critical Race Theory (CRT) even displays a hockey stick pattern of its own. Recall the popular claim on the academic left and in the media wherein CRT is merely a “moral panic” that was carefully cultivated by Rufo and other conservatives. Ngram tells a very different story, albeit with two phases. First, CRT attained modest academic adoption between its founding in the late 1980s and 2012. Then from 2013-15, it begins a hockey stick rise to the present day. 2020, the starting point of Rufo’s alleged campaign to instigate a panic, occurs after the hockey stick rise. If anything, Rufo’s attacks on CRT are a lagging indicator of an academic and journalism-driven explosion in the concept that dates to half-decade earlier.

While many of these terms refer to social and cultural concepts that find their academic home in the humanities, critical theory and its offshoots have a shared preoccupation with anti-capitalist economic beliefs. It is therefore unsurprising that most of the aforementioned hockey stick patterns have directly paralleled the rise in anti-capitalist schools of economic thought, and their associated concepts.

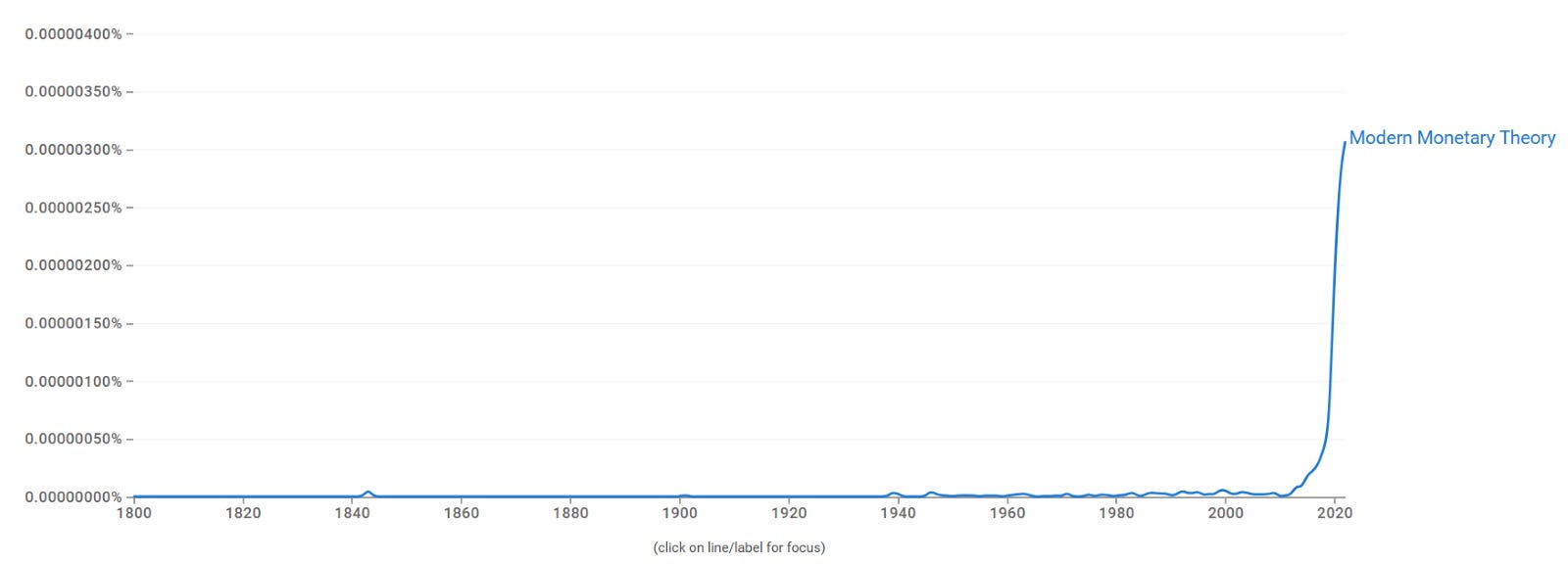

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a fringe far-left school of economics that espouses profligate deficit spending by running the printing press at the Treasury department (and attempts to blame the ensuing inflation on “corporate greed” rather than its own prescribed monetary expansion), burst into mainstream discussion with a hockey stick pattern of its own. The upward turn took place between 2014-2016, meaning it substantially postdated the 2008 financial crisis that is often credited for invigorating this heterodox school of thought. MMT has accelerated ever since, and the data show its adoption is directly concurrent with the “Great Awokening.”

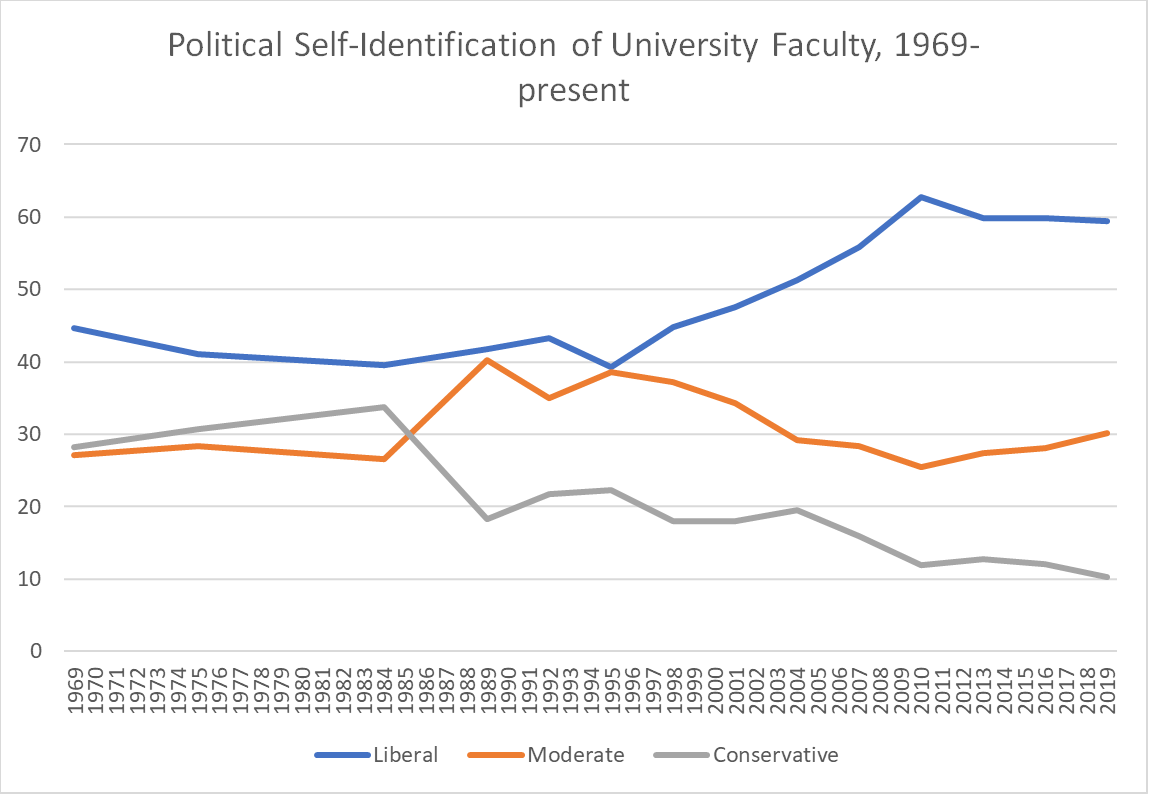

So why is the discrete period around 2014 a turning point in the hockey stick-like rise of so many proprietary terms and doctrines from the academic left? Such patterns warrant deeper investigation and empirical analysis. For the moment, I’ll propose a likely explanation rooted in the political composition of academia. For many decades, faculty identifying on the political left maintained a plurality of about 40-45% of the professoriate. At the same time, moderates and conservatives (a category that also lumps together libertarians) maintained relatively stable minority shares. Starting around 2000, faculty ideology began to shift sharply leftward. In 2004, faculty on the left attained their first-ever outright majority at 51% of the professoriate. By 2010, they had grown to a supermajority of over 60%, where it has remained ever since.

A growing emphasis on making activism a centerpiece of the university classroom also accompanied this ideological shift. In addition to tracking political identification, the nationwide HERI Faculty Survey from UCLA asks questions about pedagogy and the purpose of university instruction. One of their longest-running questions asks faculty whether their institutions prioritize “help[ing] students learn how to bring about change in American society.” In 1989, just 21 percent of faculty answered yes to this question. By 2016, the responses more than doubled to 45.8%. In 2007 the same survey added a question, asking faculty whether they saw it as their role to “encourage students to become agents of social change.” Reflecting the ongoing political shift, 57.8% answered yes. By 2016, the same question received a positive response from 80.6% of faculty. In a relatively short period of time, political activism has become a clear pedagogical priority for the professoriate.

The terminology, concepts, and doctrines that exhibit the hockey stick pattern almost all originated as proprietary jargon in the academic far-left from prior decades. The “Great Awokening” in 2014 and its immediate vicinity reflects these doctrines spilling into mainstream usage, usually following their adoption in journalism and political commentary. College students who entered the universities in the late 2000s and early 2010s coincided with the culmination of the leftward faculty shift that began a decade earlier. Their graduation dates and entry into the workforce—into journalism and media, into corporate HR departments, into the entertainment industry, and into a self-reinforcing academic environment of valorized activism and leftward politicization—coincides with the moment that the hockey stick took off.

2014, it would appear, is the year when far-left academic jargon made the leap from the faculty lounge to mainstream conversation. Any assessment of its track record in the ensuing decade should look inward to the political climate of the academy that fostered these concepts and pushed them out into the public at large. While the political right has done its own part to stoke alarm over “wokeness,” they represent a reaction to trends that were already underway. More importantly, the general public has taken notice of the language shifts of the last decade, and based on the declining trust in the institutions that promoted it, they do not like what they see.