Highlights

- The American tradition of antimilitarism—an aversion to having a large military influence on civil society—is as old as the republic itself. After the Revolutionary War, many prominent patriots opposed the idea of maintaining a peacetime army. Thomas Jefferson wrote to a friend that the new republic should maintain, not a standing army, but a naval force that “can never endanger our liberties, nor occasion bloodshed; a land force would do both.” James Monroe expressed similar views. James Madison, the father of the U.S. Constitution, was not certain that Congress possessed the authority to create a standing army. In 1783 retiring president George Washington, who came closer to advocating one than most of his contemporaries, recommended only a small regular army, to protect the frontier from Indian attacks, and a well-regulated militia.

- During wartime, antimilitarist sentiments may be suppressed by government policies, but they often rebound after the conflict ends. Nearly a decade after the War of 1812, Congress reduced the army from 10,000 to 6,000 men due to fears that preparedness would foster the resurgence of militarism. After the Civil War ended, officers and enlisted men were anxious of any delay in demobilization, and civilians became suspicious of army training, but proposals to reduce the size of the army to pre-war levels were defeated. After World War I ended, the American public entered a famous period of antiwar sentiment. A resurgence of antimilitarism took place about two decades after the end of World War II, but the military has exerted a larger influence on American life since the war than it had in previous decades.

- After World War I, civic and church groups worked diligently to end the militarization of American education. By 1925, 83 of the 123 colleges and universities that offered R.O.T.C. classes required their male students to take them. The Committee on Military Education was created to mount a public-relations campaign to end compulsory military training. With help from the Federal Council of Churches and the Methodist Episcopal Church, the Committee’s efforts led to two U.S. Supreme Court cases involving conscientious objectors who opposed compulsory R.O.T.C. at their universities. The Court upheld the requirements, but the Committee fought on and pushed for legislation to revoke federal funding of schools that compelled military training—an effort that also failed. Although the Committee did not end compulsory military training in universities, its campaign helped keep Junior R.O.T.C. out of public high schools.

- The totality of World War II and the fears of Soviet expansion worked together to set an unprecedented level of military involvement in American life during the Cold War. Fears of Soviet expansion, the totality of World War II, and other historical factors led to the military playing a much greater role in society than the country had ever before experienced during peacetime. In the realm of foreign policy, the Cold War led to scores of entangling alliances that committed the United States to defend the existing international order against those who would subvert it. Lasting over four decades and costing civil society trillions of dollars, the conflict included two “hot wars” and entailed vast continuing military budgets. As Ekirch presciently foresaw, even a peaceful resolution of the Cold War was not “sufficient to release the American people from the power of the Pentagon and its corporate allies.”

Synopsis

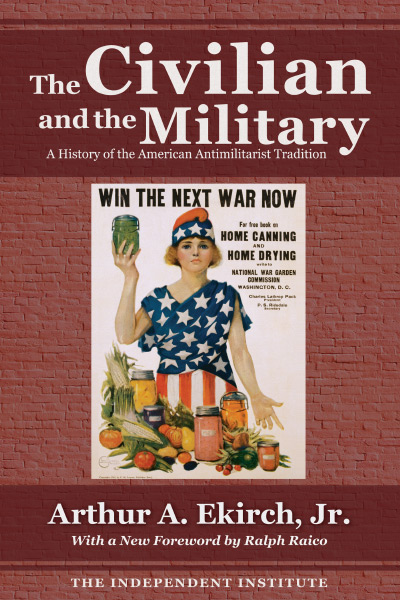

“Though involved in numerous wars, the United States has avoided becoming a militaristic nation, and the American people, though hardly pacifists, have been staunch opponents of militarism,” wrote the distinguished historian Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr., in his 1956 book, The Civilian and the Military. Subordinating the armed forces to civil rule is a tradition that is essential to the survival of freedom and democracy in America, according to Ekirch.

Now with the Independent Institute’s reissue of this book—a companion to Ekirch’s recently reissued classic, The Decline of American Liberalism—a new generation of readers can discover the nature and importance of the antimilitarist tradition as it has played out from the Founding Era to the Cold War.

As libertarian historian Ralph Raico explains in his new foreword, The Civilian and the Military traces the “portentous transformation” of the United States from a republic leery of maintaining its own standing army to “the world’s greatest military machine and sole imperial power.”

Old Traditions in the New World

Ekirch begins by tracing the American colonists’ attitudes about the military to their English origins. Due to its relative isolation, Great Britain had less need for a standing army to thwart invasions, and after its seventeenth-century revolutions, English constitutional government gained new prestige with the ultimate triumph of the principle of parliamentary supremacy. The American colonies, which were founded during this time of trouble, profited from the mother country’s experience in subordinating military power to civilian rule.

Military questions occupied a prominent place among the problems facing the United States in its early years. The Federalists sought a strong centralized government supported by a well-disciplined army of trained men. As the party of the commercial seaboard region, they also desired a navy to protect and encourage American overseas trade. In contrast, their Republican opponents, who derived support mainly from agricultural areas of the interior, viewed a permanent army or navy as instruments to benefit the merchant and trader class, and they feared that a large standing army could be used to coerce the separate states and to augment the powers of the national government.

The Republican victory of 1800 and Jefferson’s elevation to the Presidency held promise of a dramatic reversal of the Federalist policies that had dominated the first twelve years of government under the Constitution, including far-reaching changes for the army and the navy. Proponents of simplicity and economy, the Republicans were expected to oppose a strong centralized government, a large military establishment, and a naval build-up to protect American overseas commerce.

Political polarization intensified with the close of the War of 1812. Some believed that the war exerted a positive influence by spreading American nationalism and patriotism. Others believed it laid the foundation of permanent taxes and military establishments. Whereas the idealism implicit in the young republic reinforced its antimilitarist traditions and strengthened American sentiment for peace, growing nationalism stimulated expansionism and war and contributed heavily toward the development of a military point of view in the decades following the war.

The Civil War

At the outset of the Civil War the United States was not a militarist nation. But in the course of four long years of fighting between North and South, democracy was often compromised and the traditions of adherence to the rule of law and subservience of the military to civil authority faced its greatest challenge.

Some argued that the Constitution no longer operated in wartime and that “military necessity knows no law.” Over the bitter protests of a minority, who held that the government should adhere to the Constitution even in so grave a crisis as a civil war, the United States was placed under what, for all practical purposes, amounted to a military dictatorship.

The surrender of the Confederate armies preceded a groundswell of sentiment in favor of peace. In an atmosphere of conciliation, the nation turned from war to the task of reconstructing the Union. Anxious to return home and impatient of any delay in demobilization, officers and enlisted men alike revealed a strong distaste for professional army life. Now that the fighting was over, civilians were suspicious of army training and distrusted the abilities of the returning solider. Thus the Civil War served for a time to strengthen the American antimilitarist tradition.

Imperialism and Modern American Militarism

By the 1890s, the antimilitarist tradition was again threatened. The United States followed the leading industrial states of Europe by searching for world markets and colonies and developing a large navy to protect its overseas commerce. The American people faced the dilemma of trying to reconcile a new ideology of militarism and imperialism with the older values of liberalism and democracy.

The Spanish-American War marked a turning point. Previous American wars—including the Civil War—were followed by an anti-military backlash, but in 1898 the arguments of the anti-imperialists were rejected, and the United States turned toward a policy of expansion backed up by military and naval preparedness.

The call of manifest destiny and of markets across the seas was alluring. Moreover, U.S. victory in the Spanish-American War had been achieved so quickly and cheaply that it left no deep or lasting resentment. Disillusionment over U.S. policy in the Philippine Islands was too weak to counterbalance the forces that were helping to push the nation into world politics.

America and World War I

Another challenge to the American antimilitarist tradition followed the outbreak of war in 1914. Long before full U.S. participation in that conflict, the American people debated the issues of neutrality, preparedness, conscription, and general military policy. Despite the nearly unanimous initial American desire to stay out of the war, U.S. military expenditures soon climbed to unprecedented levels.

At the same time, agitation increased for military training in schools and colleges and for some system of peacetime conscription or universal service. Preparedness on such a scale, whether designed for defense or for eventual intervention, was out of keeping with historic American policy.

The advocates of preparedness talked in terms of the defense of the United States, but the real question implicit in the great preparedness debate of the spring and summer of 1916 was the possibility of American entry into the European war

Americans hailed the end of the Great War as a victory for democracy over militarism and autocracy, and many expected the United States to assume leadership in the world struggle against militarism and war. American liberals and pacifists did not, however, forget the threat of militarism at home nor the danger it posed to the preservation of peace. Particularly distressing to these groups was the increasing militarization of American education.

From Isolation to Intervention

The 1930s were a period of uncertainty and confusion. The American people and government moved from a policy of isolationist pacifism to an interventionist war program. This shift divided liberals and peace advocates in the United States. Opponents of militarism and war came to face a conflict of loyalties, forcing them to choose between their love of peace and their hatred of totalitarian dictatorships.

Despite this dilemma and the growing split within their own ranks, the peace organizations remained influential throughout the 1930s. The American people stayed largely pacifist in outlook. As Hitler’s soldiers invaded Poland, and England and France responded by declaring war on Germany, President Roosevelt issued the proclamation of neutrality required by international law and by the Neutrality Act of 1937.

When Roosevelt called Congress into special session to revise the Neutrality Act and repeal the embargo on the export of munitions, he gave his personal assurance “that by the repeal of the embargo the United States will more probably remain at peace than if the law remains as it stands today.” The guiding idea behind repeal was, of course, the desire to extend American aid to England and France in their struggle against Nazi Germany.

Toward the Garrison State

The United States—formerly among the least military of the great nations—emerged from World War II a powerfully armed state. The move toward peace that had followed earlier wars was slow to take effect. A new integration of American foreign and military policy resulted in the continued acceptance of the doctrine of peace through strength. The impact of America’s vast military commitments during the Cold War was felt at home as well as abroad.

By mid-century, the American people faced a future clouded with uncertainty. New material comforts were matched by the threat of thermonuclear warfare. The new-style, perpetual mobilization for war made all the more imperative the return of that general world peace which alone could restore any vestige of normal civil life.

Ekirch warns that the inability or refusal of the world to recognize militarism, now cloaked in civilian garb, imperils the future of both liberalism and democracy. He writes: “In the United States, where the antimilitarist tradition has been a conspicuous part of our history, it is especially pertinent to recall our national heritage and re-examine its implications for the future.”