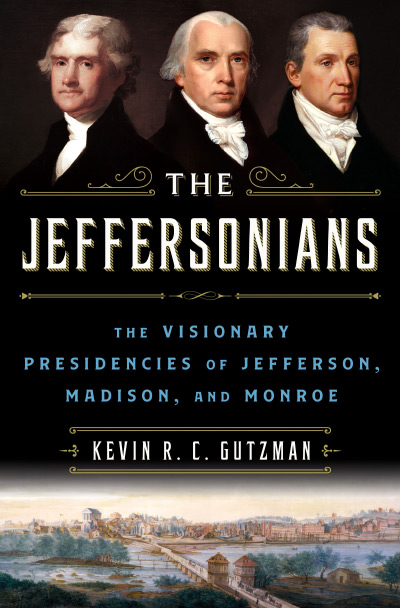

Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe represent the longest uninterrupted presidential regime in American history. These three Virginians all espoused similar political ideas, with each consciously building on the groundwork established by the one before. In just two decades, they went from one of the closest presidential elections in history to near unanimous political support in what became known as the Era of Good Feelings, despite sharp divisions among the population on most major issues. The story of how this Virginia dynasty consolidated popular support and steered the nation for so long is essential to understanding the early development of the American republic.

Kevin Gutzman’s The Jeffersonians: The Visionary Presidencies of Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe attempts to tell this story not in broad strokes, but in careful detail. It is an ambitious work of history, sweeping in its scope. The first several decades of the nineteenth century were a critical time for the United States, still a young and vulnerable republic. There were substantial questions yet to be resolved about the meaning of the Constitution and the powers of the federal government, and major debates about trade, foreign relations, military matters, elections, parties, infrastructure, among many other significant issues. Any of these alone could form the basis for a valuable book on the Jeffersonian period, but Gutzman covers them all. The book is a continuous narrative of the national politics of the United States from 1800 through 1825, and it is a compelling story.

The narrative proceeds more or less through vignettes. Each chapter is really one or two short stories about politics and history, some depicting major events and some very minor ones. For the most part, this format works very well, as Gutzman’s storytelling is well-paced and compelling. A lot of details are packed into these vignettes; the author has done prodigious research and seems to have explored all of the available source material. Some of the events could probably have been left out, but none seem superfluous or irrelevant to the general historical narrative.

On occasion in the book, though, the story is a little disjointed. For example, in a story about slave revolts in Chapter 12, Jefferson is corresponding with James Monroe, then governor of Virginia. Several pages later, Madison is corresponding with Monroe, the ambassador to Great Britain. In between there is no mention at all of the appointment, despite a brief mention of the resignation of Monroe’s predecessor in the latter post, Rufus King. A reader unfamiliar with Monroe’s career might easily be confused about why the Secretary of State would be asking the Governor of Virginia to intervene with the British government. Sometimes chapters end still in the middle of a story, and sometimes they switch storylines abruptly in the middle of a chapter. But for the most part, the various stories are told well.

The strongest sections of this book are about war. The account of the Barbary Wars is thorough and informative, and the section on the War of 1812 is even better. Gutzman explains just enough of the military actions to be able to highlight the political elements of conducting these wars. Jefferson’s efforts to build up enough of a navy to protect American shipping while in general reducing federal military expenditures are shown in detail, and Gutzman’s descriptions of the disagreements in Jefferson’s Cabinet feel almost like eyewitness accounts even where the historical evidence is fragmented. There is some speculation here, but every bit of it is plausible and persuasive, and well-supported.

Gutzman also offers excellent accounts of some of the supporting players in the Jeffersonian drama. John C. Calhoun, always a divisive figure, receives a fair and careful analysis of his roles in the Cabinet. Albert Gallatin earns extensive discussion for his often-underappreciated contributions to Jefferson as Secretary of the Treasury. And John Quincy Adams, as Secretary of State under Monroe, receives high praise despite his dubious ideological position among the Jeffersonians. Ultimately, though, the story is not about these supporting characters but about Jefferson and his immediate successors.

Jefferson himself is a divisive figure among historians. His conflicts with John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and John Marshall all practically demand taking sides. More often than not, Jefferson seems to win the sympathy of scholars studying this period, and Gutzman is no exception. His admiration of Jefferson frequently shines through, and at times this work (at least the parts focused on Jefferson) borders on hagiography. Gutzman even becomes a little defensive about Jefferson’s political legacy. At several points he seems to chastise other scholars for their poor treatment of Jefferson. For example, he claims that “most accounts of Jefferson’s foreign policy career” have a “Hamiltonian bent”; Jefferson, Gutzman insists, was looking out for U.S. interests, not French ones (p. 173). The suggestion that most historical accounts of our third President have him working as a tool for France is, at best, exaggerated, though some of his adversaries at the time made that claim.

Gutzman’s descriptions of Jefferson’s battles with Hamilton in George Washington’s cabinet reflect this same attitude, as do his explanations of the conflict with Burr in the aftermath of the election of 1800. In each case, in Gutzman’s telling, Jefferson was consistently correct in his position, and the conflict was someone else’s fault. Gutzman fully endorses Jefferson’s targeting of Samuel Chase, the “hanging judge of Messrs. Fries, Callender, and Cooper,” for impeachment (p. 159), but Jefferson’s bankrolling of Callender’s attacks on Jefferson’s political enemies escapes censure from the author. Jefferson’s falling out with John Adams was the latter’s fault in this narrative, certainly not Jefferson’s, who was prepared to mend the friendship if Adams were only less stubborn. Gutzman even goes so far as to suggest that Jefferson had satisfactorily answered the criticisms of Abigail Adams in their correspondence in 1804, a claim that no doubt would have been quite surprising to Mrs. Adams.

This defensive tendency underlies most of the section on Jefferson’s presidency, and is particularly pronounced in Gutzman’s discussion of Jefferson’s complex positions on slavery. This does not make the book less interesting, as it is packed with information and, more impressively, stories that are absolutely worth reading. It does, however, make the scholarly argument somewhat less persuasive. The book improves when Gutzman shifts to President Madison, and even more so with Monroe; neither is polarizing in quite the same way as Jefferson. Both Madison and Monroe come across as far more human than Jefferson, well-intentioned but fallible leaders doing their best for the nation. The book’s strongest contribution may well be the account of Monroe’s presidency, which has not received nearly as much scholarly attention as it deserves.

The Jeffersonians is an impressively comprehensive history of the details of our third through fifth Presidents, written in a compelling style even when the narrative gets firmly lost in those details. Ultimately, though, this is also the main weakness of the book. It aims to do so much that the amount of deep analysis is very limited. It is a wide-ranging narrative with a lot of fascinating stories, and the author manages to squeeze an impressive amount of information into 500 pages. There are no significant national political events between 1800 and 1825 that Gutzman fails to cover, but few receive more than a few pages of coverage. Despite that, it is a worthwhile read for anyone who appreciates the little details and less-known stories of American political history.

| Other Independent Review articles by Michael J. Faber | |

| Fall 2014 | James Madison and the Making of America |