| List Price: | ||

| Price: | $12.98 | |

| Discount: | $12.97 (Save 50%) |

| Formats |

Paperback |

Hardcover |

| List Price: | ||

| Price: | $12.98 | |

| Discount: | $12.97 (Save 50%) |

| Formats |

Paperback |

Hardcover |

Overview

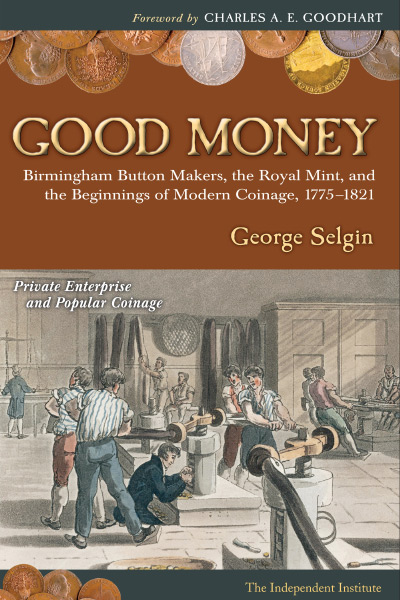

In Good Money, George Selgin tells the fascinating story of the important yet almost unknown episode in the history of money—British manufacturers’ challenge to the Crown’s monopoly on coinage.

In the 1780s, when the Industrial Revolution was gathering momentum, the Royal Mint failed to produce enough small-denomination coinage for factory owners to pay their workers. As the currency shortage threatened to derail industrial progress, manufacturers began to mint custom-made coins, called “tradesman’s tokens.” Rapidly gaining wide acceptance, these tokens served as the nation’s most popular currency for wages and retail sales until 1821, when the Crown outlawed all moneys except its own.

Good Money not only examines the crucial role of private coinage in fueling Great Britain’s Industrial Revolution, but it also challenges beliefs upon which all modern government-currency monopolies rest. It thereby sheds light on contemporary private-sector alternatives to government-issued money, such as digital monies, cash cards, electronic funds transfer, and (outside of the United States) spontaneous “dollarization.”

Contents

-

Foreword by Charles A. E. Goodhart

Preface

Prologue

1. Britain’s Big Problem

2. Druids, Willeys, and Beehives

3. Soho!

4. The People’s Money

5. The Boulton Copper

6. Their Last Bow

7. Prerogative Regained

8. Steam, Hot Air, and Small Change

9. Conclusion

Epilogue

Appendix

Sources

Index

Detailed Summary

- Although it has long been maintained that governments alone are fit to coin money, the story of coining during Great Britain’s Industrial Revolution disproves this conventional belief. In fact, far from proving itself capable of meeting the monetary needs of an industrializing economy, the Royal Mint presided over a cash shortage so severe that it threatened to stunt British economic growth. For several decades beginning in 1775, the Royal Mint did not strike a single copper coin. Nor did it coin much silver, thanks to official policies that undervalued that metal. The coins that manufacturers and wage earners were left to rely on, besides being hard to come by, were badly deteriorated and, more often than not, counterfeit.

- The cash that allowed the Industrial Revolution to reach full stride was supplied, not by Great Britain’s Royal Mint, but by private entrepreneurs. When the British government failed to ease the coin shortage, private entrepreneurs took matters into their own hands by minting their own coins. From 1787 to 1797, private merchants and industrialists issued 600 tons of custom-made “commercial” copper coin, which was more copper coin than the Royal Mint had supplied during the previous half century. The coins were struck by a score of private mintmasters, most of whom began as button makers. One of them, Matthew Boulton, owned the world’s largest and most technologically sophisticated mint, which was the first to employ steam power. In 1797 Boulton’s Soho Mint began striking copper coins on behalf of the British government, ending the Royal Mint’s monopoly of regal coinage.

- Far from being inferior to official coins, Great Britain’s commercial coins were superior to them. Besides being heavier on average than their official counterparts, commercial pennies and halfpennies generally sported superior engravings, which made them more attractive and much harder to counterfeit. Far from demonstrating Gresham’s Law, according to which “bad money drives good money from circulation,” competition in coinage did just the opposite, supplying British workers and retailers with the best money they’d ever seen. Indeed, commercial coins were so preferred to their official counterparts that merchants, once they had a choice, often refused official coins, or took them only at heavy discounts relative to their unofficial counterparts.

- The superiority of Great Britain’s commercial coinage was due, not to private mints’ superior technology, as some authorities have claimed, but to the superior incentives at play in a competitive industry. Although steam-powered coining presses are sometimes said to have been uniquely capable of making counterfeit-resistant coins, steam power was actually employed only at the Soho Mint, which manufactured less than one eighth of the commercial coins issued from 1787 to 1797. Other private mints relied on manually powered presses not unlike those long possessed by the Royal Mint. They produced superior coins, not because their machinery alone was capable to making such coins, but because competition forced them to either make good money or see their business go elsewhere.

In Good Money, George Selgin (BB&T Professor of Free Market Thought at West Virginia University; Research Fellow, The Independent Institute) tells the story of a fascinating and important yet almost unknown episode in the history of money—British manufacturers’ challenge to the Crown’s monopoly on coinage.

In the 1780s, when the Industrial Revolution was gathering momentum, the Royal Mint failed to produce enough small denomination coinage for factory owners to pay their workers. As the currency shortage threatened to derail industrial progress, manufacturers began to mint custom-made coins, called “tradesman’s tokens.” Rapidly gaining wide acceptance, these tokens served as the nation’s most popular currency for wages and retail sales until 1817, when the Crown outlawed all moneys except its own.

Good Money not only examines the crucial role of private coinage in fueling Great Britain’s Industrial Revolution, but also challenges beliefs upon which all modern government-currency monopolies rest. It thereby sheds light on contemporary private-sector alternatives to government-issued money, such as digital monies, cash cards, electronic funds transfer, and (outside of the United States) spontaneous “dollarization.”

A Dearth of Good Coin

The prologue that opens Good Money takes readers to the Welsh island of Anglesey, in the summer of 1787, where a copper miner is handed his weekly earnings only to find that they consist, not of official coins, but mainly of coins minted by his boss. They are called Parys Mine Druids, and they are only the first of many such private copper coins to come, which will supply the bulk of Great Britain’s small change for the next, crucial decade of its Industrial Revolution.

Chapter One, “Britain’s Big Problem,” explains why Great Britain’s official eighteenth-century coinage arrangements weren’t capable of supporting the needs of an industrial economy. The chapter reviews the flawed policies that caused the Royal Mint to suspend copper coin production altogether while reducing silver coinage to a mere trickle. It also recalls employers’ desperate efforts, legal and illegal, to get around the coin shortage, and how those efforts backfired by leaving workers feeling more exploited than ever.

The next chapter, “Druids, Willeys, and Beehives,” introduces Great Britain’s pioneer commercial coin makers and issuers, including Thomas “Copper King” Williams (who made the Parys Mine Druids), “Iron” John Wilkinson, and “Lunar Man” Matthew Boulton—three leading figures in Great Britain’s Industrial Revolution. It explores their true motives for getting involved in coining. (Boulton, for one, was hardly the altruistic anti-counterfeiting crusader most other authorities have made him out to be.) It also tells the rather sad story of John Westwood, one of the lesser-known private coinage pioneers.

“Soho!” tells the story of Matthew Boulton’s celebrated Soho factory and mint. When it was completed in 1789 the Soho mint (actually the first of several Soho mints) was the most sophisticated and costly mint in the world—far more sophisticated and costly than any government mint. Boulton, who was something of a megalomaniac, built it in anticipation of coining for the government, but ended up having to wait ten agonizing years before getting permission. In the meantime, he became a major producer of commercial coins.

A Commercial Coinage Regime

Once the pioneers had cleared the way, other producers and coin issuers entered the field. Chapter four, “The People’s Money,” describes the heyday of commercial coinage, from 1793 to 1797, when twenty different mints supplied coins to hundreds of commercial coin issuers around Great Britain.

The commercial coins’ marvelous engravings triggered a collecting mania that still hasn’t quit; they also helped make commercial coins much harder to counterfeit than Royal Mint products.

Commercial coins went a long way toward solving “Britain’s Big Problem,” and might have solved it altogether if the government had been willing to go on tolerating them. However, instead of promoting or at least tolerating competitive, commercial coinage, the government had other plans.

Late in 1797 Matthew Boulton finally managed to land his long-hoped-for regal coining contract, a story told in chapter five, “The Boulton Copper.” Once Boulton gained his contract, other private coiners withdrew from the business, fearing that the government was now likely to suppress their coins. Although the official copper coins Boulton produced were better than the old regal copper coinage had been, and were produced in large numbers, in many respects they proved less effective at addressing the coin shortage than commercial coins had been.

Eventually Boulton took part in the reform of the Royal Mint, equipping a brand new mint building with his steam-powered coining equipment. By doing so, Boulton unwittingly contributed to his own mint’s demise, because contrary to his expectations the government reneged on its promise to let him go on supplying British copper coin.

Suppression of Private Coinage

Despite all the Boulton copper and the new steam-powered mint at its disposal, the government still hadn’t learned how to avoid coin shortages, which grew serious again after 1810. Private coin makers and issuers once more entered the fray—the government had not bothered legally to suppress private tokens after all. During this renewal of private coinage, described in Chapter Six, “Their Last Bow,” private coin issuers, taking advantage of a precedent set by the Bank of England, took to issuing silver as well as copper coins. John Berkeley Monck, a prominent citizen of Reading, was even so bold as to issue his own gold tokens, provoking the Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval, to take steps to put an end, not only to Monck’s gold tokens, but to all private coinage.

The campaign to stamp out private coins is the subject of chapter seven, “Prerogative Regained.” Despite an outcry from merchants and industrialists all over Great Britain, and opposition from some sympathetic and influential members of Parliament, the government moved to outlaw all private coins. With only a couple of exceptions, and after several delays (forced by popular complaints), all private coin issuers were forced to retire their coins by 1817. By then the government had modified or was in the process of modifying many of its coinage policies, embracing practices pioneered by the private sector, including ones it had condemned in acting to suppress private coinage, while also drawing on the private sectors’ impressive pool of coining talent to staff the refurbished Royal Mint.

Private Enterprise and Popular Coinage

Eventually Great Britain and other nations figured out how to supply decent coin in adequate quantities. Most experts assume that the key to this success was switching from manual screw presses to steam-powered equipment (Boulton’s invention). The chapter “Steam, Hot Air, and Small Change” shows that steam power was not what mattered; nor was it what made commercial coinage successful, as several authorities have claimed. Indeed, a review of the history of steam power in Birmingham reveals that the Soho mint was the only steam powered commercial mint. It was not so much the old Royal Mint’s equipment as its policies that were to blame for Great Britain’s coin shortages. More fundamentally, a government monopoly mint simply lacks the sort of incentives that caused Great Britain’s competing private mints and coin issuers to produce coins of the highest quality and to administer their coinage system in a manner suited to the needs of industry.

The epilogue brings the story of private coinage in Great Britain up to date by describing how Ralph Heaton II purchased the contents of the last Soho Mint at auction in 1850. Heaton used that equipment to establish the Birmingham Mint, Ltd., which became the biggest private mint in the world, and survived until just recently, having been a major producer of Euro coins and blanks. In 2003, however, the Royal Mint—embittered by its failure to win a substantial share of the Euro market—took advantage of public subsidies to force its private rival out of business, violating a long-standing agreement to share foreign coining contracts with the private sector. Parliamentary investigations subsequently found the Royal Mint guilty of gross mismanagement. In December 2004, the Royal Mint’s status was changed from Treasury agency to government-owned firm in what many saw as a prelude to its privatization.

Praise

“In lucid, enjoyable, often humorous language, Selgin takes us from the ‘dark satanic mills’ to the backstreet haunts of the eighteenth-century counterfeiter and the private, legitimate mints, set up to address a problem the Royal Mint could or would not—the production of safe small change for the people. His cast of characters is large and auspicious: Thomas Williams, James Watt, John Westwood, and Matthew Boulton. And Selgin’s understanding of eighteenth-century economic theory and practice is absolute, allowing him to write with verve and clarity.”

—Richard Doty, Curator of Numismatics, Smithsonian Institution

“George Selgin’s story of how private enterprise solved a monetary problem that threatened seriously to retard the Industrial Revolution is a splendid piece of historical analysis. He has done an incredible job of unearthing all of the details of what went on in Britain in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. It is a fine example of historical research.”

—Milton Friedman, Nobel Prize Laureate in Economic Sciences

"Good Money is the kind of book that proves that economic history can be great fun in addition to instructive when written by someone who is equally knowledgeable and witty."

—Joel Mokyr, Robert H. Strotz Professor of Arts and Sciences and Professor of Economics, Northwestern University; Sackler Professorial Fellow, Eitan Berglas School of Economics, University of Tel Aviv; former Editor, Journal of Economic History

“George Selgin reveals the personalities and schemes intimately involved in creating the modern monetary system.”

—Jack Weatherford, DeWitt Wallace Professor of Anthropology, Macalester College

“Good Money is an excruciating detailed study of private mints—and I do not mean that as a back-handed criticism, but rather as an endorsement of careful, scholarly research. . . The book is laudably well-written, lively, even fascinating. Selgin displays a superb facility with the English language, and that includes contemporary as well as eighteenth-century versions. Readers will be continuously rewarded with sparks of recognition of the sources for obscure sayings, nursery rhymes, and word usages. . . . Selgin argues that the main purpose of his historical study is to cast doubt on government ventures warning that if government had usurped production of baked bread at some distant point in the past, it would probably still have a bread monopoly—no matter how inefficient its production was.”

—Journal of Economic Issues

“Good Money has a splendid mixture of monetary economics, numismatics and industrial history—with a particular focus on the central role of Birmingham in the United Kingdom's industrial revolution. While the main focus of the book, the private sector provision of copper coins in the UK, 1787–1821, may appear quite specialized, the lessons that may be drawn from it, for example about the roles of the public and private sectors in the provision of money, are much more general and wider in scope. George Selgin demonstrates a remarkable breadth and depth of scholarship in this multi-discipline work. I heartedly recommend it.”

—Charles A. E. Goodhart, Norman Sosnow Professor of Banking and Finance, London School of Economics

“Almost all previous research and publication in the two contingent fields of the history of coinage and the metal industries has formed a dichotomy between two different groups of specialists: economic historians and numismatists. . . . A great strength of this book is that Selgin has mastered both bibliographies and integrated the fields. Two further aspects of the work, which enhance its academic status, lie in the extensive deployment of primary sources (particularly the Boulton archive, the Boulton and Watt papers and the records of the Committee of the Privy Council on coin) and the wide range of themes covered. . . . The prominent sub-plot in Selgin’s book breaks surface in the introduction, the conclusion and in the robust defence of ‘genuine’ private commercial tokens. He is clearly at one with Herbert Spencer (and The Independent Institute, a promoter of private enterprise and co-publisher of the book), in challenging—or at least questioning—the claims of the state to what has always been one of the earliest, most universal, and most ruthlessly enforced public monopolies. In exploring these issues, Selgin reveals much about the dynamic of the British economy in this period and the fractious relationship between private enterprise and the apparatus of the state.”

—Economic History Review

“Good Money is a pleasure to read, and offers economic and historical scholarship of the highest quality.”

—Tyler Cowen, Director of the James Buchanan Center at George Mason University

“Good Money is a fascinating study that should appeal to the general reader ads much as to the business historian. . . . Selgin's subject is the fact that between 1787 and 1817 a deficit in the supply of coins in England was met through the private production of metal tokens that gained an acceptance as money. The most acute shortage of coins was experienced at the level of the smallest denominations. . . . [T]he main point that Selgin develops is the ability of private enterprise to compensate for an inadequacy in government provision, and to do so successfully. . . . [T]his is a well-researched book, in terms of both primary and secondary material, that tells an absorbing tale of how Britain copes with a shortage of coins during a formative period of its economic history.”

—Business History Review

“Good Money tells the riveting, forgotten, story of 18th century UK coinage: of how the Royal Mint failed to provide the small change needed to get the Industrial Revolution moving, and of how the private sector stepped in to save the day. The tale George Selgin tells is highly entertaining and challenges many of our strongest preconceptions, not just about the 18th century, but about money and coinage in general. He paints a lively and colorful picture, and the characters in his story are worthy of Hogarth himself—and, indeed, figured in many of his best caricatures. This book is an outstanding achievement, reminiscent of the best in popular history and science.”

—Kevin Dowd, Professor of Economics, University of Nottingham; co-editor, Money and the Nation State

“Good Money a major piece of work that will add greatly to our historical knowledge about coining and currency and which will bring to the fore the importance of Birmingham in the movement towards a proper currency.”

—Carl Chinn, Professor of Community History at the University of Birmingham and editor of Carl Chinn’s Brummagem Magazine

“Good Money is an impressive work of historical scholarship, informed by economics. Without polemics, it offers valuable insights into bureaucracy, innovation, and entrepreneurship. An engaging style manages to make what might seem a dull topic fascinating. George Selgin is one of the few economists I know of who takes pains to make their writing not only correct but attractive, and his conversational style helps make reading the book a pleasure. My reaction to Good Money is one of great admiration.”

—Leland B. Yeager, Ludwig von Mises Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Economics at Auburn University and Paul Goodloe McIntire Professor of Economics Emeritus at the University of Virginia

“This book tells the story of how, during the early years of the Industrial Revolution, manufacturers started minting copper coins, filling the gap left by the Royal Mint’s inability to supply the country with enough small change. George Selgin’s book brings together the themes of entrepreneurship, technological innovation and credit confidence in what is much more than a local history. . . . What makes this story interesting is that what made this promise credible were both the entrepreneurs’ reputations and the technological innovations that made counterfeiting difficult. . . . This short review cannot do justice to the richness of the material presented in Selgin’s book, and to his lucid and engaging prose. Economic and business historians and historians of technology will find it a veritable treasure trove.”

—Business History

“Good Money is a success on every level. Selgin is a better economist than most, and a better writer than most fiction writers. This is a fascinating story, or set of stories, and Selgin is a superb storyteller. The reader will feel transported back in time—especially on the ‘pub crawl’ through Birmingham towards the end of the book. This is entertaining history with many lessons for today. Savor it.”

—Bruce J. Caldwell, Rosenthal Excellence Professor of Economics at University of North Carolina at Greensboro and general editor, The Collected Works of F. A. Hayek

“Good Money challenges conventional wisdom about a subject that has recently attracted renewed attention from economists and economic historians, namely the problems that Britain encountered with its small denomination coinage in the early years of the industrial revolution. That there were indeed such problems is both well known and true; but it is also well known that the problem’s solution was found in the application of steam power to their minting, under the auspices of Matthew Boulton—the partner of no less a figure than James Watt himself—and this, Selgin argues, probably isn’t true. Thus he attacks a much-cherished myth about the history of money, and about the benevolent role played in its development by a well-established hero of the Industrial Revolution as well. Selgin suggests that the main obstacle to sound coinage in late 18th century Britain was not the absence of adequate technology, but the incompetence of the Royal Mint, and that this obstacle was well on its way to being overcome by competition from private mints when Boulton’s invention came along. No doubt Selgin’s new work will raise the hackles of those who persist in downplaying the role of competition in monetary affairs, but his research has been thorough, and his story is entertainingly told. More important, there is much of general importance about the nature of money, and the role that competition can play in providing it, to be learned from engaging with his arguments, even, perhaps particularly, for those who will at first be reluctant to accept them.”

—David E. W. Laidler, Bank of Montreal Professor at the University of Western Ontario and author of Taking Money Seriously

“I anxiously await the publication of Good Money. Taking a totally fresh approach to not only the examination of the British token coinage, but also the role of money as a medium of exchange, this is a work that will delight token collectors and general numismatists alike. Good Money is no stale academic text—I was charmed by the author's ‘Ramble 'Round Old Birmingham’ as surely as I was enlightened throughout by his meticulous research. Numismatists are readers and researchers at heart and I've no doubt that Good Money will meet with an enthusiastic response within our community."

—Harold Welch, Vice President, Conder Token Collector's Club

“George Selgin has written a fine book. His writing is a pleasure to read, and the story he tells is truly engrossing.”

—James Grant, author of Money of the Mind: Borrowing and Lending in America from the Civil War to Michael Milken

“The last decades have seen a remarkable increase in the number of books and articles devoted to the abysmal state of English regal coinage in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the development of private industrial token coinage (tradesmen’s tokens) to fill the void created by the ineptness of the Tower Mint. George Selgin’s Good Money is the very latest addition to this growing body of literature and may be counted among the more important and accessible works on the subject to date. . . . In addition to the sheer interest of the story and Selgin’s reinterpretation of several of its key aspects, Good Money is remarkable as a subtle polemic against what the author sees as the largely unnecessary and bungling control of money by modern government. . . . Regardless of whether one fully accepts the quietly polemical aspect of the book, Selgin’s probing of the evidence and keen reappraisals make Good Money required reading for specialists concerned with the British token coinage experiments of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. However, the author’s engaging and entertaining writing style also make it possible to recommend the book to anyone even remotely interested in the period of Industrial Revolution in Great Britain.”

—ANS Magazine

“Most people suppose, without having thought much about it, that money must be provided by government. That belief comes in for a sound thrashing in University of Georgia professor George Selgin’s book Good Money, which tells the story of Britain’s experience with private coinage during the Industrial Revolution. Selgin’s research shows that the government had failed to produce enough money of small denominations, how private enterprise solved the problem, and finally how the government reasserted its monopoly to put an end to the nation’s free-market money episode. . . . Good Money is a thought-provoking book. It’s also beautifully written and embellished with several glossy pages of illustrations of the coins, people, and buildings central to the story. Whether you use good money or bad, buy this wonderful book.”

—The Freeman

Author

George Selgin is a Research Fellow at the Independent Institute and BB&T Professor of Free Market Thought at West Virginia University. His research covers a broad range of topics within the field of monetary economics, including monetary theory, monetary history, macroeconomic policy, and the history of monetary thought.

He has written on these subjects for numerous journals, including the British Numismatic Journal, The Economic Journal, the Economic History Review, the Journal of Economic Literature, and the Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, as well as for The Christian Science Monitor, The Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, and other popular outlets. He is also a co-editor of Econ Journal Watch, an electronic journal devoted to exposing “inappropriate assumptions, weak chains of argument, phony claims of relevance, and omissions of pertinent truths” in the writings of professional economists. His previous books include The Theory of Free Banking (Rowman & Littlefield, 1988), Bank Deregulation and Monetary Order (Routledge, 1996), and Less Than Zero: The Case for a Falling Price Level in a Growing Economy (Institute of Economic Affairs, 1997). Professor Selgin holds a Ph.D. in economics from New York University.

Awards

2009 Independent Publisher Book Awards (“IPPY” Awards)

- Bronze Medal Winner in Finance/Investment/Economics

News

Events

| Event | Date | |

| Research Fellow George Selgin, author of Good Money speaks at Cato Annual Monetary Conference in Washington, D.C. on November 17, 2016 | Thu., Nov. 17, 2016 |