| List Price: | ||

| Price: | $11.48 | |

| Discount: | $11.47 (Save 50%) |

| List Price: | ||

| Price: | $11.48 | |

| Discount: | $11.47 (Save 50%) |

Overview

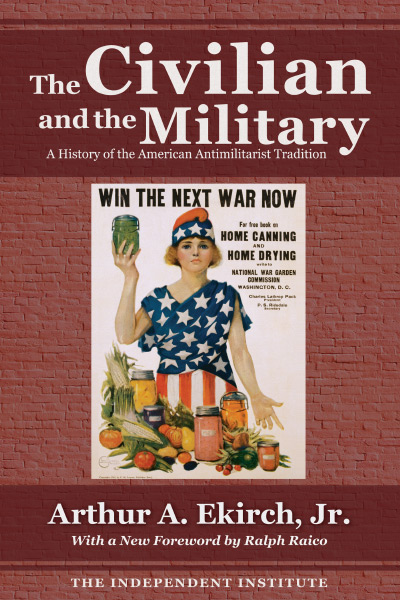

This book is an account of the rise and decline of the antimilitarist tradition that has been an important part of the American heritage from its beginning in colonial times. This tradition, with its emphasis upon civil rather than military authority, is accepted as an essential element of American freedom and democracy. By elaborating on the role of the civilian and the military in American history up until the 1950s, the author helps us understand why the growing power and importance of the armed forces over many aspects of national and international policy is alarming for thoughtful citizens and policy makers today.

From the Foreword

As Ekirch presciently foresaw, even a peaceful resolution of the Cold War was not “sufficient to release the American people from the power of the Pentagon and its corporate allies.” Incursions of the armed forces occurred in Yugoslavia, the Philippines, Somalia, and elsewhere. Now the United States is involved in wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Yemen, soon perhaps also in Iran.

Today there is no conscription, which caused too many problems for the militarists in the Vietnam years. But the American empire bestrides the globe. The United States has over 700 military bases overseas, plus some dozen naval task forces patrolling the oceans, with a multitude of space satellites feeding information to the forces below. Every year its “defense” (i.e., military) budget is nearly equal to those of all other countries combined. Does anyone doubt that for America there are more wars, many more wars, in the offing?

As Joseph Schumpeter wrote of the military in imperialist states: “Created by the wars that required it, the machine now created the wars it required.”

Read the Foreword by Ralph Raico

Contents

-

Foreword by Ralph Raico

Preface to the 1972 Edition

Introduction

Acknowledgments

I. The Anglo-American Heritage

II. The Founding Fathers Reaffirm Civil Supremacy

III. The Defeat of the Federalist Military Plans

IV. The Jeffersonian-Republican Surrender

V. A More Militant Nationalism and Growing Pacifism

VI. A Military Hero and Manifest Destiny

VII. The Menace of Civil War

VIII. The Reconstruction of Civil Socieity

IX. The New Threat of Imperialism and Navalism

X. Theodore Roosevelt and Modern American Militarism

XI. European Militarism and American Preparedness

XII. Conscripting America for War

XIII. Disillusionment and Partial Disarmament

XIV. Militarism in Education

XV. The Hope of Isolation and Neutrality

XVI. Immersion in Total War

XVII. Toward the Garrision State

Bibliographical Comment

Notes

Index

Detailed Summary

- The American tradition of antimilitarism—an aversion to having a large military influence on civil society—is as old as the republic itself. After the Revolutionary War, many prominent patriots opposed the idea of maintaining a peacetime army. Thomas Jefferson wrote to a friend that the new republic should maintain, not a standing army, but a naval force that “can never endanger our liberties, nor occasion bloodshed; a land force would do both.” James Monroe expressed similar views. James Madison, the father of the U.S. Constitution, was not certain that Congress possessed the authority to create a standing army. In 1783 retiring president George Washington, who came closer to advocating one than most of his contemporaries, recommended only a small regular army, to protect the frontier from Indian attacks, and a well-regulated militia.

- During wartime, antimilitarist sentiments may be suppressed by government policies, but they often rebound after the conflict ends. Nearly a decade after the War of 1812, Congress reduced the army from 10,000 to 6,000 men due to fears that preparedness would foster the resurgence of militarism. After the Civil War ended, officers and enlisted men were anxious of any delay in demobilization, and civilians became suspicious of army training, but proposals to reduce the size of the army to pre-war levels were defeated. After World War I ended, the American public entered a famous period of antiwar sentiment. A resurgence of antimilitarism took place about two decades after the end of World War II, but the military has exerted a larger influence on American life since the war than it had in previous decades.

- After World War I, civic and church groups worked diligently to end the militarization of American education. By 1925, 83 of the 123 colleges and universities that offered R.O.T.C. classes required their male students to take them. The Committee on Military Education was created to mount a public-relations campaign to end compulsory military training. With help from the Federal Council of Churches and the Methodist Episcopal Church, the Committee’s efforts led to two U.S. Supreme Court cases involving conscientious objectors who opposed compulsory R.O.T.C. at their universities. The Court upheld the requirements, but the Committee fought on and pushed for legislation to revoke federal funding of schools that compelled military training—an effort that also failed. Although the Committee did not end compulsory military training in universities, its campaign helped keep Junior R.O.T.C. out of public high schools.

- The totality of World War II and the fears of Soviet expansion worked together to set an unprecedented level of military involvement in American life during the Cold War. Fears of Soviet expansion, the totality of World War II, and other historical factors led to the military playing a much greater role in society than the country had ever before experienced during peacetime. In the realm of foreign policy, the Cold War led to scores of entangling alliances that committed the United States to defend the existing international order against those who would subvert it. Lasting over four decades and costing civil society trillions of dollars, the conflict included two “hot wars” and entailed vast continuing military budgets. As Ekirch presciently foresaw, even a peaceful resolution of the Cold War was not “sufficient to release the American people from the power of the Pentagon and its corporate allies.”

“Though involved in numerous wars, the United States has avoided becoming a militaristic nation, and the American people, though hardly pacifists, have been staunch opponents of militarism,” wrote the distinguished historian Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr., in his 1956 book, The Civilian and the Military. Subordinating the armed forces to civil rule is a tradition that is essential to the survival of freedom and democracy in America, according to Ekirch.

Now with the Independent Institute’s reissue of this book—a companion to Ekirch’s recently reissued classic, The Decline of American Liberalism—a new generation of readers can discover the nature and importance of the antimilitarist tradition as it has played out from the Founding Era to the Cold War.

As libertarian historian Ralph Raico explains in his new foreword, The Civilian and the Military traces the “portentous transformation” of the United States from a republic leery of maintaining its own standing army to “the world’s greatest military machine and sole imperial power.”

Old Traditions in the New World

Ekirch begins by tracing the American colonists’ attitudes about the military to their English origins. Due to its relative isolation, Great Britain had less need for a standing army to thwart invasions, and after its seventeenth-century revolutions, English constitutional government gained new prestige with the ultimate triumph of the principle of parliamentary supremacy. The American colonies, which were founded during this time of trouble, profited from the mother country’s experience in subordinating military power to civilian rule.

Military questions occupied a prominent place among the problems facing the United States in its early years. The Federalists sought a strong centralized government supported by a well-disciplined army of trained men. As the party of the commercial seaboard region, they also desired a navy to protect and encourage American overseas trade. In contrast, their Republican opponents, who derived support mainly from agricultural areas of the interior, viewed a permanent army or navy as instruments to benefit the merchant and trader class, and they feared that a large standing army could be used to coerce the separate states and to augment the powers of the national government.

The Republican victory of 1800 and Jefferson’s elevation to the Presidency held promise of a dramatic reversal of the Federalist policies that had dominated the first twelve years of government under the Constitution, including far-reaching changes for the army and the navy. Proponents of simplicity and economy, the Republicans were expected to oppose a strong centralized government, a large military establishment, and a naval build-up to protect American overseas commerce.

Political polarization intensified with the close of the War of 1812. Some believed that the war exerted a positive influence by spreading American nationalism and patriotism. Others believed it laid the foundation of permanent taxes and military establishments. Whereas the idealism implicit in the young republic reinforced its antimilitarist traditions and strengthened American sentiment for peace, growing nationalism stimulated expansionism and war and contributed heavily toward the development of a military point of view in the decades following the war.

The Civil War

At the outset of the Civil War the United States was not a militarist nation. But in the course of four long years of fighting between North and South, democracy was often compromised and the traditions of adherence to the rule of law and subservience of the military to civil authority faced its greatest challenge.

Some argued that the Constitution no longer operated in wartime and that “military necessity knows no law.” Over the bitter protests of a minority, who held that the government should adhere to the Constitution even in so grave a crisis as a civil war, the United States was placed under what, for all practical purposes, amounted to a military dictatorship.

The surrender of the Confederate armies preceded a groundswell of sentiment in favor of peace. In an atmosphere of conciliation, the nation turned from war to the task of reconstructing the Union. Anxious to return home and impatient of any delay in demobilization, officers and enlisted men alike revealed a strong distaste for professional army life. Now that the fighting was over, civilians were suspicious of army training and distrusted the abilities of the returning solider. Thus the Civil War served for a time to strengthen the American antimilitarist tradition.

Imperialism and Modern American Militarism

By the 1890s, the antimilitarist tradition was again threatened. The United States followed the leading industrial states of Europe by searching for world markets and colonies and developing a large navy to protect its overseas commerce. The American people faced the dilemma of trying to reconcile a new ideology of militarism and imperialism with the older values of liberalism and democracy.

The Spanish-American War marked a turning point. Previous American wars—including the Civil War—were followed by an anti-military backlash, but in 1898 the arguments of the anti-imperialists were rejected, and the United States turned toward a policy of expansion backed up by military and naval preparedness.

The call of manifest destiny and of markets across the seas was alluring. Moreover, U.S. victory in the Spanish-American War had been achieved so quickly and cheaply that it left no deep or lasting resentment. Disillusionment over U.S. policy in the Philippine Islands was too weak to counterbalance the forces that were helping to push the nation into world politics.

America and World War I

Another challenge to the American antimilitarist tradition followed the outbreak of war in 1914. Long before full U.S. participation in that conflict, the American people debated the issues of neutrality, preparedness, conscription, and general military policy. Despite the nearly unanimous initial American desire to stay out of the war, U.S. military expenditures soon climbed to unprecedented levels.

At the same time, agitation increased for military training in schools and colleges and for some system of peacetime conscription or universal service. Preparedness on such a scale, whether designed for defense or for eventual intervention, was out of keeping with historic American policy.

The advocates of preparedness talked in terms of the defense of the United States, but the real question implicit in the great preparedness debate of the spring and summer of 1916 was the possibility of American entry into the European war

Americans hailed the end of the Great War as a victory for democracy over militarism and autocracy, and many expected the United States to assume leadership in the world struggle against militarism and war. American liberals and pacifists did not, however, forget the threat of militarism at home nor the danger it posed to the preservation of peace. Particularly distressing to these groups was the increasing militarization of American education.

From Isolation to Intervention

The 1930s were a period of uncertainty and confusion. The American people and government moved from a policy of isolationist pacifism to an interventionist war program. This shift divided liberals and peace advocates in the United States. Opponents of militarism and war came to face a conflict of loyalties, forcing them to choose between their love of peace and their hatred of totalitarian dictatorships.

Despite this dilemma and the growing split within their own ranks, the peace organizations remained influential throughout the 1930s. The American people stayed largely pacifist in outlook. As Hitler’s soldiers invaded Poland, and England and France responded by declaring war on Germany, President Roosevelt issued the proclamation of neutrality required by international law and by the Neutrality Act of 1937.

When Roosevelt called Congress into special session to revise the Neutrality Act and repeal the embargo on the export of munitions, he gave his personal assurance “that by the repeal of the embargo the United States will more probably remain at peace than if the law remains as it stands today.” The guiding idea behind repeal was, of course, the desire to extend American aid to England and France in their struggle against Nazi Germany.

Toward the Garrison State

The United States—formerly among the least military of the great nations—emerged from World War II a powerfully armed state. The move toward peace that had followed earlier wars was slow to take effect. A new integration of American foreign and military policy resulted in the continued acceptance of the doctrine of peace through strength. The impact of America’s vast military commitments during the Cold War was felt at home as well as abroad.

By mid-century, the American people faced a future clouded with uncertainty. New material comforts were matched by the threat of thermonuclear warfare. The new-style, perpetual mobilization for war made all the more imperative the return of that general world peace which alone could restore any vestige of normal civil life.

Ekirch warns that the inability or refusal of the world to recognize militarism, now cloaked in civilian garb, imperils the future of both liberalism and democracy. He writes: “In the United States, where the antimilitarist tradition has been a conspicuous part of our history, it is especially pertinent to recall our national heritage and re-examine its implications for the future.”

Praise

"Once upon a time, Republican presidents worried about deficit spending and were reluctant to be talked into unnecessary defense expenditures by lobbyists inflating threats. Large peacetime military establishments were considered risks to American democracy and security. President Dwight Eisenhower shared these concerns sufficiently to warn in his valedictory address about the "unwarranted influence" of ‘the military-industrial complex’—a warning that reflected his background in industrial mobilization and his experience in office. He came under enormous pressure to authorize the purchase of expensive military systems, often by retired officers who had joined corporate boards. In Unwarranted Influence, Ledbetter traces how the speech came about and charts its later influences, refuting those who claimed it sank without trace. A companion piece from the same period is a reprint of Ekirch's 1956 book The Civilian and the Military. Scholarly in its research and scope, the book also celebrates that antimilitaristic tradition, with its hostility to standing armies and conscription, warmongering by ‘merchants of death,’ distorted budgetary priorities, and the subversion of individual freedom in the name of national security. It reveals, often unintentionally, the problems with this tradition (notably, how to deal with states that are even more militaristic) while providing a compelling reminder of its historic influence."

—Foreign Affairs

“This is a well-written history of the anti-military tradition in the United States. It is a useful corrective to current tendencies in American political and historical scholarship: for instance, it is well to be reminded that military fervor played an important part in Andrew Jackson’s popular support and that, however commendable and timely was Theodore Roosevelt’s interest in world affairs, one of its motive forces was a romantic passion for things martial. Professor Ekirch has chronicled American attitudes about military institutions from pre-Revolutionary times—with an ‘Anglo-American heritage’; of anti-militarism—to the Eisenhower Administration. With few exceptions, whatever he has included in his chronicle he has presented dispassionately. And he has done enough digging to make his work valuable for general scholarly reference. His book is a significant addition to the growing literature on American military affairs. . . The author has done some thoughtful and careful work.”

—The American Political Science Review

“The author develops the story of antimilitarism concretely, not only in terms of periodic wars, but also in terms of peacetime debates over military appropriations, the size and nature of the armed forces, and the role of the military in civilian affairs. He traces the preference for civil supremacy to England, shows how it was reinforced by colonial experience, and how it became part of the fundamental law of the land. So far so good. But from the time of the War of 1812, as Professor Ekirch sees it, the advocates of militarism had a downhill run, through the Mexican War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, and the three wars of the twentieth century. In our day the line between the civilian and the military has been completely obliterated; militarism is everywhere, in government, industry, education, even in scientific research. We now have a garrison state with the entire population either directly or indirectly enrolled in some military capacity. To Professor Ekirch this heralds the end of our free society, for he agrees with David Starr Jordan that ‘as militarism grows democracy must die.’ . . . Even those who disagree with Professor Ekirch will commend him for calling attention to the problem of civilian-military relations, and for reminding us that this juncture of our history of the democratic implications of our antimilitarist tradition.”

—Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science

“This book deals with the plowshare, rather than the sword....He finds the origin of [the antimilitarist tradition] in our Anglo-American heritage and traces its effect from our colonial days to the present.”

—Military Affairs

“One upon a time, Republican presidents worried about deficit spending and were reluctant to be talked into unnecessary defense expenditures by lobbyists inflating threats. Large peacetime military establishments were considered risks to American democracy and security. President Dwight Eisenhower shared these concerns sufficiently to warn in his valedictory address about the ‘unwarranted influence’ of ‘the military-industrial; complex’—warning that reflected his background in industrial mobilization and his experience in office. . . . A companion piece from the same period is a reprint of Ekirch’s 1956 book The Civilian and the Military. Scholarly in its research and scope, the book also celebrates that antimilitaristic tradition, with its hostility to standing armies and conscription, warmongering by ‘merchants of death,’ distorted budgetary priorities, and the subversion of individual freedom in the name of national security.”

—Foreign Affairs

“Extensive research in contemporary sources went into the preparation of this volume. From colonial times to the present, proposals to train the militia more effectively, to enlarge the standing army, or to build naval vessels are treated as examples of expanding militarism. ”

—The Journal of Politics

“This book deals with the plowshare, rather than the sword. The sub-title, A History of the American Antimilitarist Tradition, accurately describes its contents. The author defines the antimilitarist as one who accepts wars and armies as a sometimes necessary evil, but regards a large military establishment and conscript armies, even when needed, as a threat to the preservation of civil institutions of government. He finds the origin of this feeling in our Anglo-American heritage and traces its effect from our colonial days to the present. By quoting from a variety of published sources he documents the influence of this tradition in keeping our military establishment small until we were actually at war. He finds that some of our wars, notably the War of 1812 and the Mexican War, were unpopular with many Americans because of our antimilitarist tradition. Much resistance to the Union and Confederate governments during the Civil War was motivated, he believes, by the force of this tradition. Similarly, he shows that our antimilitarist traditions have been responsible for the rapid demobilization of our military establishments at the close of each of our wars. The concluding chapter of the book describes the current state of our antimilitarist tradition. The author states that the events since World War II gave the American people ‘little hope of any sudden return to real peacetime modes of living,’ and that this has modified the antimilitarist traditions of the American people.”

—Journal of the American Military Institute

“Mr. Ekirch, professor of history at the American University and author of other works on different phases of the intellectual history of the United States, has contributed a careful survey of antimilitaristic thinking throughout American history. . . . He is content to summarize the record of antimilitarism, which he is careful to distinguish from absolute pacifism. . . . Professor Ekirch writes as an uncompromising antimilitarist, although he grants that the typical one ‘has opposed expansion overseas on intervention in world affairs’. The story he tells shows clearly enough that Jefferson and others who have been of the author’s general persuasion when out of power have changed their minds when charged with the responsibilities of office and forced to deal with the facts of international political life. . . . [H]e has generally written with fully professional competence. He has undertaken to summarize the record of American antimilitaristic thnking and he has produced a readable and useful digest.”

—The American Historical Review

“The growing power and importance of the military office and personnel over all aspects of national life in recent years has been a cause of alarm to many thoughtful citizens. Mr Ekirch, professor of history at American University, has been concerned for a decade or more with this problem. . . . Now we have a book-length history of the antimilitarist tradition in the United States from colonial times until the present. This tradition, with its emphasis upon the civilian as against the military authority, is viewed as an important factor in shaping American history and a vitally essential element of our freedom and democracy. It is, in the author’s opinion, gravely imperiled. Notable issues and landmarks in the struggle for civilian supremacy and in opposition to militarism are discussed; debates about the role of the militia and the size of the standing army, the level of army and navy appropriations, the establishment of R.O.T.C. units, and the adoption of compulsory conscription are placed in their historical setting; pertinent legislation and much private and public discussion support the story. Emerging from the account is the view that the American tradition of antimilitarism has suffered gradual decline from revolutionary times and markedly so since 1900. . . . The pages of his book reflect the convictions of the author: an avowed antimilitarist who naturally finds little solace in recent developments; a student of history who would share with Dean Louis Smith the conviction that a redress in the balance between civilian and military authority should be urgently sought after; a pessimist who looks with nostalgia to the early days of the republic and who might well hold Jefferson as his hero; an intellectual historian whose writings should give pause to those who blindly believe in the idea of progress; a realist. For he concludes his book with these sentences apropos of the future facing the United States at mid-century: ‘The new style perpetual mobilization for war made all the more imperative the return of that general world peace which alone could restore any vestige of normal civil life. Only in such an atmosphere could the American tradition of antimilitarism, peace, and democracy flourish and continue to be a vital, living force for the future.’ The truly challenging question, but beyond the scope of the book as set by the author, is what can be done to achieve this general world peace without which there seems little hope of escape from the trend toward the garrison state.”

—Journal of American History

“This nation was born with a universal conviction that standing armies, however necessary, are ‘ever dangerous to the liberties of the people.’ It has reached a point at which it is maintaining colossal standing armed forces, peacetime conscription, a huge intervention of strategic factors into the civilian economy and policy, and other stigmata of the garrison state. Mr Ekirch has written a history of this striking transformation. With patience he has recovered and recorded the military programs, the debates, the enactments, which have steadily expanded the military factor in our affairs—his book is, indeed, useful as a history of American military policy. Together with this he has searched out the names and words of innumerable people, great and small, individually or in groups, who have opposed this process for one reason or another—pacifists, liberals, opposition politicians, anti-imperialists, money-savers, socialists, Quakers, draft-dodgers and many more. The resultant study is of value; it is almost painfully erudite, and illuminates a number of obscure corners in our military-political history. . . . The history has much of real usefulness and interest.”

—Political Science Quarterly

“Ekirch seems to step off from certain immovable assumptions about what is good in human existence and about the incompatibility of that good with what he calls ‘militarism’ and ‘militarists.’ This good, when spoken of in one word, seems to be ‘liberal.’ . . . Professor Ekirch’s The Civilian and the Military records—with voluminous documentation—the history of antimilitarism (opposition to preparedness of any sort) in our country. He and his sources tolerate the Revolutionary War as marginally acceptable since it got us started as a nation, and particularly since it was fought in a more ‘liberal’ way with hundreds of thousands of short-timers, rather than with professionals. . . . All other uses of armed force after the Revolution, and programs to provide therefore, are questionable in his eyes and the opposition thereto (but not the case for) is carefully recorded in this book. But The Civilian and the Military is a useful book, if only that it reminds us that this tradition of antimilitarism is an important factor in our past and still conditions some areas of public opinion today. . . . Revisionist historians interpreting the history of the World War II period should read and heed this book. It contributes to an understanding of why we probably could not have reaped a better harvest from our victory even if our leadership had had the vision of these historians’ 20-20 hindsight. . . . Professor Ekirch, who teaches at American University, seems to accept that the traditional fear of a military takeover, Cromwell style, no longer exists, but he points with alarm to the dangers of present-day ‘militarism’ (i.e., what others call preparedness, readiness, and so forth) to our society and institutions. This pointing is not to be lightly disregarded. Certainly $40-billion national security budgets, 7 million civilians who have been conditioned overseas in uniforms, an officer corps ranking in size with the major professions, some industries materially dependent on the security effort, increasing numbers of influential retired personnel—these things and dozens of others deserve the most careful study.”

—Public Administration Review

“In 1798, Benjamin Rush suggested that over the portals of the War Department there be painted the caption: ‘An office for butchering the human species.’ In 1956, the characteristic public image of a large armed force is of an instrument for maintaining peace by its deterrent effect on potential aggressors. Thus has the American anti-militarist tradition succumbed to hot and cold war influences in the view of Professor Ekirch. His book is an excellent, thorough chronological account of American opinion, pro- and anti-, regarding the place of military organization and military ideas. He describes a constant struggle to avoid militarism in the United States from colonial times to the present. He concludes that we are closer to an acceptance of militarism now than ever before. Particularly good are the chapters on liberal capitulation to war policies in 1917, on the inter-war struggles to eliminate compulsory military training from the campuses, and on the tendencies toward militarism inherent in the cold war. . . . [A]s a case study of changing public images and the propaganda efforts involved, The Civilian and the Military is a valuable contribution on a topic of much current interest.”

—The Public Opinion Quarterly

“Extensive research in contemporary sources went into the preparation of this volume.”

—The Journal of Politics

"Ekirch, a libertarian historian best known for his book The Decline of American Liberalism, reminds us of the vehement anti-military (not just anti-militaristic) sentiments that suffused the founding of the American republic and lived into the 20th century. Ekirch explains that centralism and militarism worked like a hammer and anvil to destroy the small-R American republican tradition. In an era where elites from the party that calls itself 'Republican' unanimously demand that the American military police the world, Ekirch reminds us that the Founders would have made Code Pink sound like Dick Cheney."

—Justin Logan, Director of Foreign Policy Studies, Cato Institute

Author

Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr. was a leading scholar of American intellectual history, Professor Emeritus of History at the State University of New York, Albany, and founding Member of the Board of Advisors of the Independent Institute. He was the author of numerous books including the following list: The Idea of Progress in America 1815–1860, The Decline of American Liberalism, Man and Nature in America, The American Democratic Tradition: A History, Voices in Dissent: An Anthology of Individualist Thought in the U.S., Ideas, Ideals and American Diplomacy: A History of Their Growth and Interaction, Ideologies & Utopias: The Impact of the New Deal on American Thought, American Intellectual History: The Development of the Discipline, The Challenge of Democracy: A Concise History of Social Thought and Political Action, Progressivism in America: A Study of the Era from Theodore Roosevelt to Woodrow Wilson.